Understanding introversion

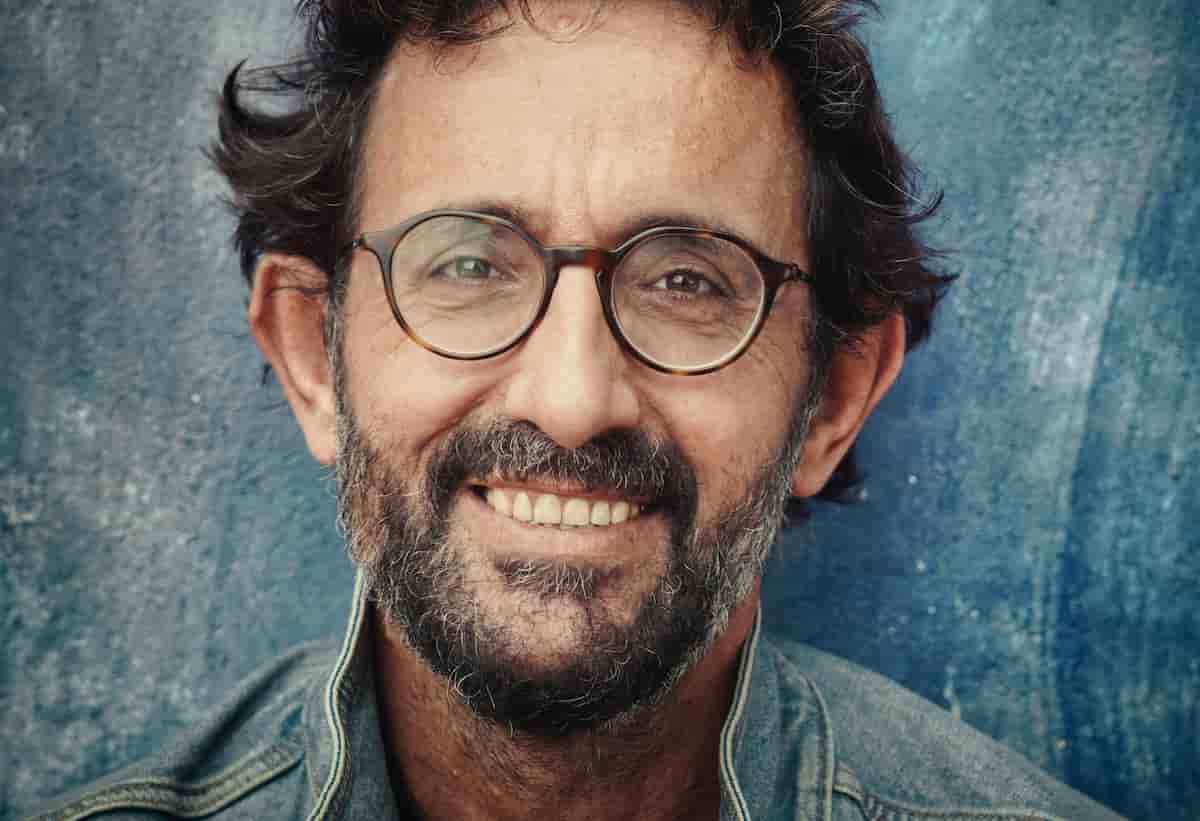

Introversion is a personality trait characterised by a preference for quieter, less stimulating environments.

Contrary to popular belief, introverts are not necessarily shy or antisocial.

Instead, they draw energy from solitude and introspection.

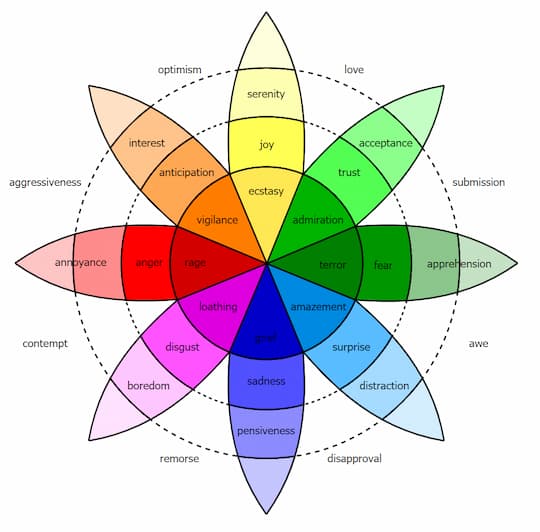

The concept of introversion is often compared to extroversion, creating a spectrum on which individuals may fall.

Key traits of introverts

- Enjoy spending time alone or in small groups

- Feel drained by prolonged social interactions

- Prefer deep conversations over small talk

- Are highly reflective and self-aware

These traits can vary in intensity, making every introvert unique.

Some may display strong preferences for solitude, while others enjoy socialising in controlled or meaningful ways.

Introversion vs extroversion

While extroverts are energised by social interactions, introverts find solace in solitude.

This does not mean introverts dislike people but rather that they recharge in different ways.

It is important to note that introversion and extroversion are not binary but exist on a spectrum, with ambiverts falling somewhere in between.

Signs you might be an introvert

Preference for solitude

If you enjoy spending time alone and feel content without constant social interaction, you might be an introvert.

Solitude allows introverts to reflect, recharge, and engage in activities they find fulfilling.

Feeling drained after social interactions

Introverts often need time to recharge after attending social events, even if they enjoy the experience.

This recovery period is crucial for maintaining their energy and emotional balance.

Need for quiet to concentrate

Distractions can be particularly bothersome for introverts, who tend to thrive in calm, focused environments.

This preference for quiet can enhance their productivity and creativity, especially in tasks requiring deep thought.

Reflective and self-aware nature

Many introverts spend time reflecting on their thoughts and feelings, leading to a deep sense of self-awareness.

This introspection often results in personal growth and a clearer understanding of their goals and values.

Common misconceptions about introverts

Introverts are shy

Shyness and introversion are not the same.

Shyness is a fear of social judgement, whereas introversion is about energy preferences.

While some introverts may be shy, many are confident in social situations when they feel comfortable.

Introverts dislike people

Introverts often enjoy meaningful connections but may prefer quality over quantity in their relationships.

They value deep, authentic interactions and often form strong bonds with close friends and family members.

Introverts lack leadership skills

Many introverts make excellent leaders due to their thoughtful, empathetic, and strategic approaches.

They are skilled at listening, observing, and making well-considered decisions, which can inspire trust and respect.

Thriving as an introvert

Leveraging introverted strengths

Introverts excel in roles that require deep thinking, creativity, and careful planning.

Recognising these strengths can help introverts thrive personally and professionally.

Examples include careers in writing, research, art, and technology, where their ability to focus and innovate shines.

Self-care strategies for introverts

- Set aside time for solitude

- Create a calm, personal space

- Engage in activities that foster creativity and relaxation

These practices can help introverts maintain their well-being and avoid burnout.

Navigating social situations

Preparing for social interactions can help introverts feel more comfortable.

Setting boundaries and allowing time to recharge are also essential strategies.

Introverts might benefit from focusing on smaller gatherings or one-on-one interactions that feel more manageable.

Introversion in relationships

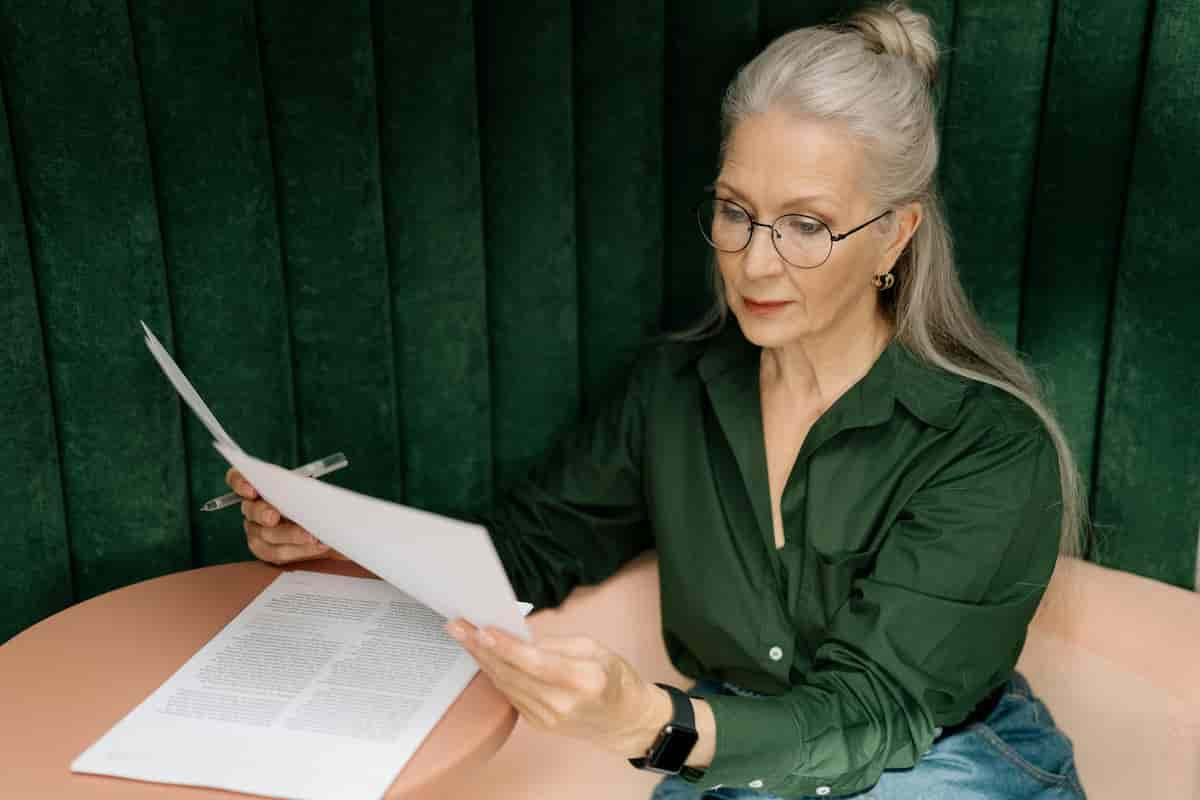

Communication styles of introverts

Introverts often favour deep, meaningful conversations over casual chatter.

They may take time to open up but value genuine connections.

Understanding this communication style can foster stronger relationships.

Introvert-extrovert dynamics

Relationships between introverts and extroverts can be fulfilling, as each brings unique strengths to the partnership.

While introverts may encourage reflection and thoughtfulness, extroverts can bring energy and spontaneity.

Supporting an introverted partner

Understanding an introverted partner’s need for solitude and respecting their boundaries can strengthen relationships.

Communicating openly about each person’s preferences can help navigate differences and build trust.

Personal growth for introverts

Embracing your introverted nature

Accepting and valuing introversion as a strength can lead to greater self-confidence and fulfilment.

Acknowledging what makes you unique allows you to harness your strengths effectively.

Overcoming challenges as an introvert

Learning to communicate needs and assert boundaries are crucial steps for personal and professional growth.

Introverts can also work on stepping out of their comfort zones in ways that feel authentic and manageable.

Setting boundaries and prioritising well-being

Introverts can benefit from recognising their limits and prioritising activities that align with their energy levels.

This might include scheduling downtime after busy periods or saying no to events that feel overwhelming.

Introversion in the workplace

Introverts as leaders

Many introverts possess qualities such as active listening and thoughtful decision-making, which make them effective leaders.

Their ability to remain calm under pressure and consider multiple perspectives is invaluable in leadership roles.

Creating an introvert-friendly work environment

Workplaces that value independent work, quiet spaces, and flexibility are ideal for introverts.

Providing opportunities for remote work or private offices can enhance productivity for introverted employees.

Balancing collaboration and independent work

Introverts can thrive by balancing teamwork with opportunities for focused, individual contributions.

This balance allows them to contribute meaningfully without feeling drained by excessive social interaction.

Understanding ambiverts

Ambiverts exhibit qualities of both introverts and extroverts, making them adaptable to various situations.

They can enjoy social interactions while also appreciating the value of alone time.

Understanding the differences between these traits can help individuals better navigate their own personalities and relationships.

Conclusion

Introversion is a valuable and often misunderstood trait that contributes significantly to the diversity of human personalities.

By understanding and embracing introversion, individuals can leverage their strengths, navigate challenges, and build meaningful relationships and fulfilling careers.

Whether you are an introvert or know someone who is, recognising the unique qualities of this personality type can foster greater empathy and appreciation.