The bystander effect describes a psychological phenomenon where individuals are less likely to help in an emergency when others are present.

What is the bystander effect?

The bystander effect refers to the tendency for individuals to refrain from offering help in emergencies when others are present.

This phenomenon arises from a belief that someone else will intervene or that their own involvement is unnecessary.

Psychologists Bibb Latané and John Darley first studied this behaviour in the 1960s, coining the term “diffusion of responsibility” to describe the dynamic at play.

When people witness an emergency as part of a group, they may experience a reduced sense of personal responsibility, leading to inaction.

This effect can occur in various settings, from public spaces to online platforms, and is a crucial concept in understanding human behaviour in group dynamics.

The Kitty Genovese case: myths and realities

The bystander effect gained widespread attention following the 1964 murder of Kitty Genovese in New York City.

Initial reports claimed that dozens of her neighbours witnessed her attack and failed to call for help, reflecting widespread apathy.

This narrative was later criticised for inaccuracies and exaggerations, but the case still served as a catalyst for psychological research into group behaviour.

While the sensationalised story painted a bleak picture of human inaction, it also spurred significant societal discussions about the need for intervention and accountability.

Psychologists have since explored how such cases can be used to educate the public about the importance of individual responsibility in emergencies.

Psychological roots of the bystander effect

Diffusion of responsibility

Diffusion of responsibility is a key factor in the bystander effect.

When others are present, individuals feel less pressure to act because they believe someone else will take responsibility.

This shared responsibility dilutes individual accountability, making intervention less likely.

The presence of a group creates a psychological safety net, which can paradoxically lead to collective inaction.

Pluralistic ignorance

Pluralistic ignorance occurs when individuals interpret others’ inaction as a sign that intervention is unnecessary.

For example, in ambiguous situations, people often look to those around them for cues on how to behave.

If no one else acts, they may assume the situation is not serious, even if they initially believed otherwise.

This misinterpretation can reinforce a cycle of inaction, perpetuating the bystander effect.

Fear of judgment

Another contributing factor is the fear of social judgement or embarrassment.

People may hesitate to intervene out of concern that their actions could be deemed inappropriate or unnecessary.

This fear is particularly strong in public settings, where individuals feel their behaviour is being closely scrutinised.

By understanding these psychological mechanisms, we can develop strategies to overcome the barriers to intervention.

Beyond the lab: real-life manifestations

The bystander effect is not confined to psychological experiments.

It appears in various real-world contexts, from emergencies on the street to instances of cyberbullying.

Emergencies in public spaces

In crowded environments like train stations or busy streets, individuals often fail to help strangers in distress.

This is especially common when the situation appears ambiguous, such as when someone collapses but shows no clear signs of injury.

The assumption that “someone else will handle it” prevents prompt assistance, even in life-threatening situations.

Cyberbullying and online behaviour

The bystander effect also extends to digital spaces, where people witness harmful behaviour online but choose not to intervene.

This may involve ignoring cyberbullying, hate speech, or misinformation.

The anonymity of the internet can amplify the diffusion of responsibility, making it easier for individuals to avoid taking action.

Understanding how the bystander effect operates in these contexts is vital for designing interventions that encourage active participation.

Overcoming the bystander effect: tools for action

Training programmes

Educational initiatives play a crucial role in countering the bystander effect.

Workshops and training sessions can teach people how to recognise emergencies and respond effectively.

For instance, bystander intervention training often includes role-playing scenarios to build confidence and familiarity with helping behaviours.

Raising awareness

Public awareness campaigns can highlight the importance of individual action in preventing harm.

By educating the public about the psychological barriers to intervention, such campaigns empower individuals to overcome their hesitation.

Simple messages like “If you see something, say something” can have a profound impact.

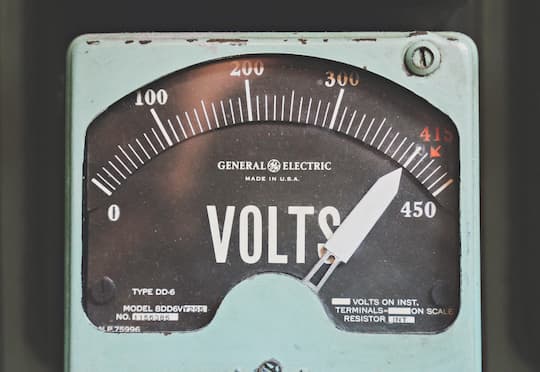

Technological innovations

Technology offers new tools to combat the bystander effect.

Mobile apps that facilitate quick and anonymous reporting of emergencies reduce the barriers to action.

Social media platforms can also be used to promote awareness and share success stories, encouraging a culture of active intervention.

Bystander effect in the workplace

The bystander effect is not limited to public emergencies; it can also occur in professional environments.

Addressing harassment and discrimination

In workplaces, employees may hesitate to report harassment or discrimination, assuming someone else will step forward.

Bystander intervention training can equip staff with the skills to address inappropriate behaviour, fostering a safer work environment.

Building supportive cultures

Creating a culture of accountability and support reduces the likelihood of inaction.

Encouraging employees to speak up and providing clear reporting mechanisms can counteract the diffusion of responsibility.

Organisations that prioritise these values are more likely to prevent and address workplace issues effectively.

Inspiring active bystanders: success stories

While the bystander effect highlights inaction, numerous examples show that individuals can rise to the occasion.

Stories of people stepping in to save lives or stand up against injustice serve as powerful reminders of our potential to make a difference.

These success stories often involve individuals who overcame fear or hesitation, demonstrating the value of courage and empathy.

By sharing these narratives, we can inspire others to take action when it matters most.

Implications for society: creating a culture of care

The bystander effect offers important lessons for society as a whole.

By addressing the psychological barriers to intervention, we can create a culture that values responsibility and care.

Policies that promote education, awareness, and accountability are essential for reducing inaction and encouraging proactive behaviour.

Ultimately, overcoming the bystander effect requires collective effort, but it begins with individual action.

By choosing to act, we can break the cycle of inaction and contribute to a more compassionate world.

This comprehensive exploration of the bystander effect highlights its psychological roots, real-world manifestations, and strategies for change.

Through education, awareness, and inspiring stories, we can all become active participants in fostering a more caring society.