People used the app for an average of just under one hour a day.

Keep reading with a Membership

• Read members-only articles

• Adverts removed

• Cancel at any time

• 14 day money-back guarantee for new members

People used the app for an average of just under one hour a day.

The words were linked to conditions like depression and anxiety.

The internet is radically changing people’s memory, attention and social skills.

Almost all of a person’s satisfaction with life has nothing to do with using social media.

It reduced depression and PTSD risk by 50%.

Why the world feels more dangerous, despite getting safer.

Which types of emotional tweets are most contagious?

Which types of emotional tweets are most contagious?

Tweets containing positive emotions are most likely to spread virally, a new study finds.

Scientists analysed 3,800 randomly chosen Twitter users.

They wrote a program to automatically classify the emotional value of the tweet: positive, negative or neutral.

Then the software tracked how the tweet did, socially, in comparison to the usual sort of tweets that person sent.

The results showed that across all the users, it was positive tweets that were more contagious than negative ones.

Around 20% of people were also highly susceptible to emotional contagion.

After reading more negative tweets, this 20% produced more negative tweets.

Still, it was positive tweets that had the greatest influence.

A study last year found similar results for Facebook:

“Emotions expressed online — both positive and negative — are contagious, concludes a new study from the University of California, San Diego and Yale University (Coviello et al., 2014).

One of the largest ever studies of Facebook examined the emotional content of one billion posts over two years.

Software was used to analyse the emotional content of each post.

[…] [They found that] positive emotions spread more strongly, with positive messages being more strongly contagious then negative.They found that each additional positive post led to 1.75 more positive posts by their Facebook friends.

The authors think, though, that even this may be an underestimation of the power of emotional contagion online.

The new study was published in the journal PLOS ONE (Ferrara & Yang et al., 2015).

Tweet image from Shutterstock

People usually search out positive posts on social media — but not always.

People usually search out positive posts on social media — but not always.

People who are in a bad mood spend more time searching social media for others who are doing worse than they are, a new study finds.

This goes against the usual trend that people look mainly for posts that are generally positive and uplifting.

This is because how we compare ourselves to others has a powerful effect on how we feel — but it depends on our motivation.

Upward comparisons to those who are doing better than us can be beneficial when people are in a good mood, but they can be depressing when we are already feeling down.

Benjamin Johnson, who co-authored the study, said:

“People have the ability to manage how they use social media.

Generally, most of us look for the positive on social media sites.

But if you’re feeling vulnerable, you’ll look for people on Facebook who are having a bad day or who aren’t as good at presenting themselves positively, just to make yourself feel better.”

The conclusions are based on a study which put 168 people into either a good or bad mood by telling them they’d done well — or poorly — on a test (Johnson & Knobloch-Westerwick, 2014)

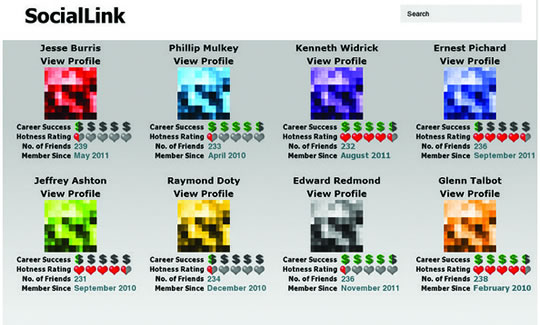

Afterwards they were asked to review a new social networking site, that the researchers called SocialLink.

There were eight profiles on the site, some made to look more attractive and successful than others.

Here is what participants saw:

The faces were pixelated out so that participants wouldn’t be influenced by people’s actual appearance, but had to go on the ‘heart’ and ‘dollar sign’ ratings below them.

The profiles themselves were generic, with little to distinguish between them.

The results showed that, in general, people looked more at the profiles of people who had been rated more successful and attractive.

But, those who were in a negative mood spent more time looking at the profiles of those rated less successful and less attractive.

The study’s co-author, Silvia Knobloch-Westerwick, said:

“If you need a self-esteem boost, you’re going to look at people worse off than you.

You’re probably not going to be looking at the people who just got a great new job or just got married.

One of the great appeals of social network sites is that they allow people to manage their moods by choosing who they want to compare themselves to.”

Image credit: CollegeDegrees360 & Johnson & Knobloch-Westerwick.

Study in which Facebook manipulated the news feeds of almost 700,000 users for psychological research sparks controversy.

Study in which Facebook manipulated the news feeds of almost 700,000 users for psychological research sparks controversy.

A new study of ‘emotional contagion‘ which manipulated the Facebook news feeds of 689,003 users for a week in 2012 has been widely criticised over ethical and privacy concerns.

Facebook users who ‘took part’ in the experiment did not give their consent, either before or after their news feeds were manipulated.

In fact, you may have taken part without knowing anything about it.

Working with researchers at Cornell University and the University of California, San Francisco, Facebook subtly adjusted the types of stories that appeared in user’s news feeds for that week (Kramer et al., 2014).

Some people saw stories that were slightly more emotionally negative, while others saw more content that was slightly more emotionally positive.

People were then tracked to see what kind of status updates they posted subsequently.

One of the study’s authors, Jeff Hancock, explained the results:

“People who had positive content experimentally reduced on their Facebook news feed, for one week, used more negative words in their status updates.

When news feed negativity was reduced, the opposite pattern occurred: Significantly more positive words were used in peoples’ status updates.”

In other words: positive and negative emotions are contagious online.

The study echoes that conducted recently by Coviello et al. (2014), which found that positive emotions are more contagious than negative.

The previous study, though, while it was conducted on Facebook in a somewhat similar way, did not manipulate users’ news feeds, rather it used random weather variations to make a natural experiment:

“…they needed something random which would affect people’s emotions as a group and could be tracked in their status updates — this would create a kind of experiment.

They hit upon the idea of using rain, which reliably made people’s status updates slightly more negative.” (Happiness is Contagious and Powerful on Social Media)

There are all sorts of conversations going on about whether or not this experiment was sound.

Media outlets have been scrambling around to see what various rules have to say about this.

Was the study’s ethical procedure correctly reviewed? Did Facebook break its terms of service?

But let’s just forget the rules for a moment and use our brains:

The reason people are jumping on the story is because of concerns about what other people are doing with our data, especially big corporations and governments.

Take Facebook itself: many people don’t realise that Facebook is already manipulating your news feed.

The average Facebook news feed has 1,500 items vying for a spot in front of your eyeballs.

Facebook doesn’t show you everything, so it has to decide what stays and what goes.

To do this they use an algorithm which is manipulating your news feed in ways that are much less transparent than this experiment.

Professor Susan Fiske of Princeton University, who edited the article for the academic journal it was published in (PNAS), told The Atlantic:

“I was concerned until I queried the authors and they said their local institutional review board had approved it—and apparently on the grounds that Facebook apparently manipulates people’s News Feeds all the time… I understand why people have concerns. I think their beef is with Facebook, really, not the research.”

But should our justifiable concerns about being spied on, manipulated and exploited stop researchers conducting a harmless and valuable psychology experiment?

Final word goes to the study’s lead author, Adam Kramer, a Data Scientist at Facebook, who was moved to apologise:

“The reason we did this research is because we care about the emotional impact of Facebook and the people that use our product.

We felt that it was important to investigate the common worry that seeing friends post positive content leads to people feeling negative or left out.

At the same time, we were concerned that exposure to friends’ negativity might lead people to avoid visiting Facebook.

We didn’t clearly state our motivations in the paper.”

Image credit: Dimitris Kalogeropoylos

87% of US teachers think the internet is creating a distracted generation. Is it really true?

87% of US teachers think the internet is creating a distracted generation. Is it really true?

There’s no evidence that typical levels of internet use harms adolescent brains, according to a new review of 134 studies.

On the contrary, the report, to be published in the journal Trends in Cognitive Science, finds some positives associated with normal internet use (Mills, 2014).

Many of the scare stories about the effects of the internet on the brain are based on studies of those using it excessively, which only affects around 5% of adolescents.

The perception that internet use is eroding young people’s attention spans certainly exists:

“Of the 2462 American middle- and high-school teachers surveyed by the Pew Research Center, 87% felt that widespread Internet use was creating an ‘easily distracted generation with short attention spans’ and 88% felt that ‘today’s students have fundamentally different cognitive skills because of the digital technologies they have grown up with’.” (Mills, 2014)

There is, however, no consistent, hard evidence of any damaging effects of the internet on the cognitive powers of young people, or other aspects of their development.

In fact, this review points to some of the benefits of using the internet. For example, studies have found:

As for ‘internet addiction’, here’s what I have to say about that: Does Internet Use Lead to Addiction, Loneliness, Depression…and Syphilis?

Mills concludes her article:

“In the 25 years since the World Wide Web was invented, our way of interacting with each other and our collective history has changed.

Successfully navigating this new world is likely to require new skills, which will be reflected in our neural architecture on some level.

However, there is currently no evidence to suggest that Internet use has or has not had a profound effect on brain development.”

The real answer to what the internet is doing to our brains is: it depends on what we’re doing with the internet.

Here’s how I put it in a recent article, which focused on Facebook:

“Consider Facebook for a moment.

There are all kinds of things you can do: stalk old partners, play games, find fascinating content, keep in touch with old friends or look at random pictures of other people’s drunken nights out (not all of these are recommendations).

People’s creativity in using online services streaks way ahead of our knowledge of what it means and how it affects us.

In fact, we’re only just starting to see studies that make more fine-grained distinctions about what people are actually doing online and how that may, or may not, be good for them.”

Finally, it’s worth remembering that — as Mills says — finding little evidence is different from finding that there is no effect; rather it means that more research needs to be carried out into typical levels of internet use.

Image credit: Spaceman photography

Join the free PsyBlog mailing list. No spam, ever.