Positive affirmation exercises can boost confidence in the self, kickstart behaviour change, improve self-control and even IQ.

Positive affirmation exercises are mantras that one repeats to oneself in the hope that they will become true.

These could include self-love affirmations, affirmations for success, daily affirmations or even morning affirmations, such as:

- I love myself.

- I am confident.

- I am relaxed in social situations.

- Today will be a good day.

Some people recommend positive affirmations for anxiety, depression and other mental health conditions.

While positive affirmations are often seen as merely New Age or self-help gimmicks, legitimate psychological research has found they can be effective, if used in a specific way.

Scientific use of positive affirmations

The way that scientists have examined positive affirmations is in terms of ‘self-affirmations’.

Self-affirmations involve confirming or declaring one’s own personal beliefs.

For examples, have a look at the following list of values and personal characteristics.

If you had to pick just one, which most defines who you are and what matters to you?

- Your family

- Being good at sports

- Belief in a higher power

- Your friends

- Your creativity

- Aesthetics

- Your job

Perhaps what matters most to you isn’t there, in that case think about what does matter to you most.

In studies on self-affirmation, participants are asked to write a paragraph or two on why this characteristic or value is so important to them.

Sometimes they also think about a specific time or story that is illustrative.

The effects can be surprisingly effective across a large number of domains.

Below are some examples of where scientists have found that positive affirmations can be useful.

1. Boost confidence with self-affirmations

Self-affirmation can boost performance for people who are put in positions of low power.

Thinking or writing about your family, your strengths or something that is important to you boosts confidence and performance.

This can even work when self-affirming or using positive affirmations about a situation which is apparently irrelevant.

Dr Sonia Kang, an organisational psychologist at the University of Toronto, who led the study, said:

“Writing down a self-affirmation may be more effective than just thinking it, but both methods can help.

Before a performance review, an employee could write or think about his best job skills.

Writing or thinking about one’s family or other positive traits that aren’t associated with the high-stakes situation also may boost confidence and performance.

Anytime you have low expectations for your performance, you tend to sink down and meet those low expectations.

Self-affirmation is a way to neutralize that threat.”

2. Positive affirmations for behaviour change

When given advice about how to change, people are often automatically defensive, trying to justify their current behaviour.

Messages about eating healthier, doing some exercise and all the rest may be rejected by stock defences, like not having enough time or energy.

But, research has found that focusing on values that are personally important — such as helping a family member — can help people act on advice they might otherwise find too threatening.

One study, published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Science, scanned people’s brains as they were given typical advice about exercise you might get from any doctor (Falk et al., 2015).

Before receiving the advice, though, some were led through a self-affirmation exercise involving positive affirmations.

This simply involves thinking about what’s important to you — it could be family, work, religion or anything that has particular meaning.

The researchers were interested in activity in part of the brain called the ventromedial prefrontal cortex (VMPFC).

The results showed that people who had used these positive affirmations beforehand displayed more activity in the VMPFC, suggesting they had taken the advice to heart.

Not only that, but their activity levels over the next month did increase more than the group who had not used positive affirmations.

3. Affirmations increases social confidence

For people low in social confidence, a feeling of apprehension about meeting new people is outwardly expressed as nervous behaviour and this leads to rejection.

In other words, people low in social confidence often get exactly what they expect.

However, self-affirmation or positive affirmations can help to boost social confidence, research has found.

For one study, participants looked down a list of 11 values including things like spontaneity, creativity, friends and family, personal attractiveness and so on (Stinson et al., 2011).

They put them in order of importance and wrote a couple of paragraphs saying why their top-ranked item was so important.

The results showed that this simple task boosted the relational security of insecure individuals in comparison with a control group.

Afterwards their behaviour was seen as less nervous and they reported feeling more secure.

And when they were followed up at four and eight weeks later, the benefits were still apparent.

It appears that even a task as simple as this is enough to boost the social confidence of people who feel insecure.

4. Self-control renewed by positive affirmations

Failures of self-control, however, have been linked with addiction, overeating, interpersonal conflict and underachievement.

Self-control can be hard to maintain, as most of us know to our cost.

Self-affirmation, through positive affirmations, can help, though, research finds.

Some participants in one study were asked to write about their core values, e.g. their relationship with their family, their creativity or their aesthetic preferences, whatever they felt was important to them (Schmeichel & Vohs, 2009).

They were then given a classic test of self-control: submerging their hand in a bucket of icy cold water, which, if you’ve ever tried it, you’ll know becomes very painful after a minute or two.

The results showed that people who had used positive affirmations were able to hold their hand under water for more than twice as long as those who had not used a positive affirmation.

One reason positive affirmations may work is that thinking about core values puts our minds into an abstract, high-level mode.

This has been found to increase self-control.

5. Positive affirmations boost IQ by 10%

Recalling a past success could be enough to raise IQ by 10 percent, a study has found (Hall et al., 2014).

People who were asked to use positive affirmations improved their cognitive functioning by an amount equivalent to 10 IQ points.

The study was carried out on people living in poverty.

Almost 150 people in a New Jersey soup kitchen were asked to record a personal story of a past success — this was their positive affirmation.

It was designed to see if a simple procedure could help them overcome the powerful stigma and low self-worth they were experiencing.

Professor Jiaying Zhao, who led the study, said:

“This study shows that surprisingly simple acts of self-affirmation improve the cognitive function and behavioral outcomes of people in poverty.”

6. Problem-solving improved by positive affirmations

A simple positive affirmation exercise can have a beneficial effect on problem-solving under stress, particularly for individuals who have been stressed recently (Cresswell et al., 2013).

Half the participants did the positive affirmation exercise while the rest performed a similar, but ineffectual exercise.

The results showed that those who had been stressed recently and were using positive affirmations before they began the exercise performed better at the problem-solving task.

This suggests that positive affirmations could be useful for people under stress who are, for example, taking exams, going to job interviews or under pressure at work.

What’s fascinating about the positive affirmations task is that it doesn’t have to be related to the area in which you’re looking to improve.

So thinking about the importance of your family can increase your problem-solving performance, even though the two have little in common.

7. Self-affirmations increase motivation

There are even ways to boost the effect of positive affirmations.

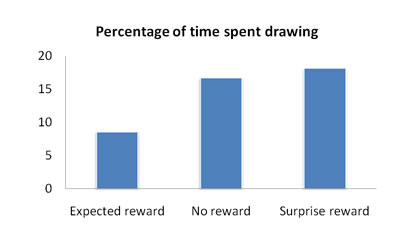

One study has found that asking yourself a question helps boost motivation more than simple positive affirmations (Senay et al., 2010).

In other words: “Will I exercise?” works better than “I will exercise.”

In the study, one group of people told themselves they would complete an anagram task (this is a positive affirmation).

The other group, though, asked themselves whether they would complete the task.

The results showed that those who asked themselves the question solved more anagrams than those who ordered themselves.

Further experiments showed that the questioning approach helped to boost internal or ‘intrinsic’ motivation.

Psychologist have found that internal motivation is the strongest type.

It is fascinating how a simple change to language like this can help boost motivation.

Professor Dolores Albarracin, one of the study’s authors, said:

“The popular idea is that self-affirmations enhance people’s ability to meet their goals.

It seems, however, that when it comes to performing a specific behavior, asking questions is a more promising way of achieving your objectives.”

Why positive affirmations work

We don’t know exactly why positive affirmation exercises works, some options include that it improves people’s mood or that they engaged more with the task.

However, one likely explanation is that positive affirmations help you move your attention more flexibly, which improves memory function.

Whatever the mechanism, this growing body of evidence on the benefits of self-affirmation is encouraging.

.