Types of motivation, how to stay motivated and the biggest myth about motivation.

Motivation is what causes animals to start or stop doing something.

People generally use the term motivation to describe ‘why’ people do things.

However, people have all sorts of motivational states in their minds — many of which are not put into action.

For most people, the things we are motivated to do, but resist, probably far outweigh the things we end up doing.

So, motivation is not just about action or inaction, it is also about competing mental states.

Psychologists have put forward all sorts of theories about why people do things, including drive theory, instinct theory and humanistic theory.

The truth, though, is that people’s motivation is difficult to assess, partly because so much of it is unconscious.

Types of motivation

One useful distinction, though, in motivation, is between intrinsic and extrinsic motivation.

For human beings, roughly speaking there are only two reasons to do anything in life:

- Because you want to: known to psychologists as intrinsic motivation.

- Because someone else wants you to: what psychologists call extrinsic motivation.

The first category of internally motivated activities might include things like eating, socialising, hobbies and going on holiday.

The second category of externally motivated activities might include working a job, studying, or loading the dishwasher.

The reason I say ‘roughly speaking’ and ‘might include’ is because the two types of motivation can be difficult to disentangle.

Yes, you enjoy your work, but would you do it for less money or for free?

Maybe, maybe not.

Yes, my wife wants me to load the dishwasher, but maybe I’d do it anyway.

Or maybe not.

Turning work into play

One type of motivation can slowly morph into another over time.

For example, things originally we did for their own sake can become a chore once we are paid for them.

More hearteningly, sometimes things we once did just for the money can become intrinsically motivated.

This latter, magical transformation is most fascinating and probably happens because the activity satisfies one or all of three basic human needs.

As the eminent motivation researchers, Richard M. Ryan and Edward L. Deci, say, it’s these three factors that are at the core of intrinsic motivation (Ryan & Deci, 2000):

- Competence. We want to be good at something. Things that are too easy, though, don’t give us a sense of competence; it has to be just hard enough.

- Autonomy. We want to be free and dislike being controlled. When people have some freedom—even within certain non-negotiable boundaries—they are more likely to thrive.

- Relatedness. As social animals we want to feel connected to other people.

Look for these in any activity if you want to harness the power of self-guiding, internal motivation.

How to stay motivated

Completing a long-term project takes different types of motivation as time passes.

Studies find that people motivate themselves in different ways depending on where they are in pursuing a goal (Bullard & Manchanda, 2017).

At the start, people motivate themselves with hopes and dreams of reaching their goal.

For example, someone wanting to lose weight might think about the clothes they will be able to wear.

Psychologists call this ‘promotion motivation’ as the study’s authors explain:

“Promotion motivation encourages people to focus on hopes and aspirations, it makes people think of their goals in terms of attainment of something positive, and it leads individuals to favor approach-oriented “eager” strategies in goal pursuit.”

Some tips to help you get motivated at the start of a project include:

- Reward yourself for taking the first steps.

- Note some positive things you will gain from completing the project.

However, as people get closer to their goal, they get more defensive.

Psychologically, it becomes less about the benefits and more about avoiding a slip-up:

“…prevention motivation encourages people to focus on responsibilities and duties, it makes people think of their goals in terms of avoiding something negative, and it leads individuals to favor avoidance-oriented “vigilant” strategies in goal pursuit.”

Some tips to help you get motivated as the end of the project nears:

- List problems to avoid.

- Write down the barriers to completing the goal.

- Give yourself a break if things get too hard.

- Focus on your duty to finish the project and why it is so important.

Tips for increasing motivation

Many people are looking for ways to increase their motivation and psychologists have done a lot of research in this area.

Here are some common ways studies have found motivation can be boosted.

1. Use the stick for motivation

To change people’s behaviour, the stick beats the carrot, but it only needs to be a small stick, research finds (Kubanek et al., 2015).

The study compared the effects of punishments (stick) with rewards (carrot) to see which worked best.

The psychologists found the influence of punishments outweighed rewards by two or three times.

Bear in mind, though, that continuous negative feedback has all sorts of other effects so it should be used sparingly.

2. Switch tasks to recover motivation

Most people’s motivation and performance starts to dip after doing a difficult task for around 30 minutes (Randles et al., 2017).

As people get closer to one hour on a task, there is very noticeable drop in performance.

However, if people switch tasks, their self-control is less limited than many believe.

This is why short, effortful bursts can be so effective.

3. Use self-talk for motivation

Thinking “I can do better” really can help improve performance (Lane et al., 2016).

Self-talk like this increases the intensity of effort people make and even makes them feel happier as well.

The study compared the motivational power of self-talk, such as “I will do better” with imagery and if-then planning.

Imagery involved imagining doing better and if-then planning is making a plan to act in a certain way.

All three techniques improved performance, but self-talk was consistently the most powerful.

4. Create backup plans

Backup plans are a useful way of driving you forward at the precarious early stages of a project.

That’s because our motivation to succeed is heavily tied in with our expectations of success.

No one drives to a shop that they are pretty sure is closed.

What feeds our motivation is knowing that we have a good chance of achieving the goal.

A little more time spent thinking about a backup plan or alternative ways to get where you’re going will help you, even if you never have to actually use them (Huang & Zhang, 2013).

However, backup plans do not work as well when a project is well underway.

Towards the end, backup plans should be reduced to avoid distraction.

5. Use fear

Fear can be used as an excellent motivator for exercise, research finds (Sobh & Martin, 2007).

When people imagine themselves getting fat and unattractive, they are more motivated to work out.

Fear seems to work particularly well when people are failing at their goals.

In the study, fear motivated 85 percent to continue with their gym programme when they were failing.

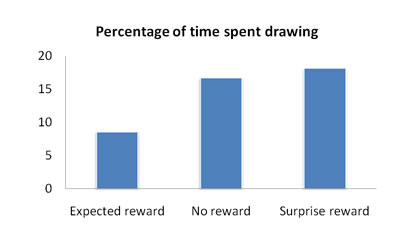

The biggest myth about motivation

One of the single biggest myths about motivation that most people firmly believe is that cash incentives increase motivation.

If you want the job done well, offer a bonus — or so the common belief goes.

In fact, psychological research often shows the opposite (Murayama et al., 2016).

When psychologists test the effects of using rewards, they find something strange.

People are indeed motivated by rewards in the short-term.

But, in the long-term rewards actually undermine motivation.

Dr Kou Murayama, first author of a study, said:

“Society has a deep-rooted misunderstanding of how motivation works, and employers are repeatedly shooting themselves in the foot with the frequent use of rewards to encourage certain behaviours or increase effort.

Our work shows we need to correct our strong misbelief in a carrot and stick approach to achieve sustained motivation among workers.”

The study involved people playing a game — some were offered rewards to play again, others not.

Almost two-thirds of people agreed that incentives would motivate people.

Actually the reverse was true: rewards demotivated people.

The reasons seemed to be that:

- People’s autonomy is undermined by rewards. In other words they think if they are being paid to do something, they don’t really want to do it for its own sake.

- People focus more on the reward than actually doing the job.

Instead of rewards, it is better to focus on internal motivation and people’s personal autonomy should be respected.