Study of 3,000+ finds men and women process emotions differently and this affects what they remember.

Women rate emotional images as more stimulating and are more likely to remember them than men, a new study finds.

While strong emotions tend to boost memory for both men and women, this neuroimaging study may help explain why women often outperform men on memory tests.

The results come from a very large study of 3,398 people who took part in four different trials.

Both men and women were asked to look at a series of pictures, some of which were emotionally arousing and others which were neutral.

They were also tested on their memory for the pictures.

The results, published in the Journal of Neuroscience, showed that women found the emotional pictures — and especially the negative pictures — more stimulating than the men (Spalek et al., 2015).

Dr Klara Spalek, the study’s first author, said:

“This result would support the common belief that women are more emotionally expressive than men.”

Across all the pictures women displayed enhanced recall, and their memory was particularly good for the positive images.

Dr Annette Milnik, who led the study, said:

“This would suggest that gender-dependent differences in emotional processing and memory are due to different mechanisms.”

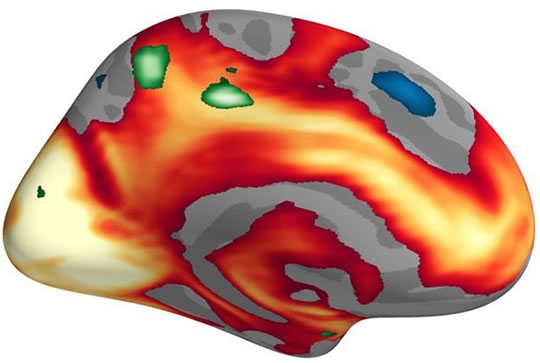

The researchers then examined brain scans which were taken while people looked at different types of emotional images.

This showed that women’s brains were more active in appraising the negative images than men, especially in the parts of the brain linked to motor functions.

In the image below, the red and yellow areas show the parts of the brain which were more active in both men and women when they looked at emotionally stimulating images.

The green shows the specific areas where women’s brains were more active.

Image credit: Ryan Wiedmaier & MCN, University of Basel