Working memory plays a crucial role in our daily cognitive processes, influencing everything from learning and reasoning to decision-making.

What is working memory?

Working memory refers to the brain’s ability to temporarily hold and manipulate information needed for cognitive tasks.

Unlike short-term memory, which merely stores information for a brief period, working memory actively processes and uses that information.

It helps us perform tasks like solving math problems, following instructions, and engaging in conversations.

Working memory is often described as a mental workspace where information can be accessed, used, and updated in real time.

It allows us to juggle multiple pieces of information simultaneously, which is critical for complex reasoning and problem-solving.

The components of working memory

The central executive

This is the control system that directs attention and coordinates the flow of information between different components of working memory.

It is responsible for prioritising tasks, switching between them, and inhibiting distractions to maintain focus.

The phonological loop

The phonological loop deals with spoken and written material.

It consists of two parts: the phonological store, which retains sound-based information, and the articulatory rehearsal system, which allows us to repeat information in our minds.

This component is crucial for language learning, reading comprehension, and verbal reasoning.

The visuospatial sketchpad

This component processes visual and spatial information.

It is essential for tasks such as navigating a route or visualising an object.

It plays a significant role in activities that require mental imagery, such as solving puzzles or drawing diagrams.

The episodic buffer

The episodic buffer integrates information from the other components and links it with long-term memory.

It helps create a unified representation of experiences.

This integration allows for more complex cognitive functions, such as forming coherent narratives and making sense of events.

Theories and models of working memory

Baddeley’s model of working memory

This widely accepted model includes the central executive, phonological loop, visuospatial sketchpad, and episodic buffer.

It highlights the complexity of working memory and its multifaceted nature.

Each component works together to support diverse cognitive activities.

Cowan’s embedded-processes model

Cowan’s model emphasises the role of attention in working memory.

It suggests that working memory capacity is determined by the focus of attention rather than separate storage systems.

This theory provides a framework for understanding individual differences in memory performance.

Development of working memory

Working memory in childhood

Working memory capacity develops significantly during childhood and adolescence.

Children with strong working memory skills often perform better academically.

Deficits in working memory can lead to challenges in reading comprehension, problem-solving, and following multi-step instructions.

Young children rely heavily on working memory to acquire new skills, such as reading and arithmetic.

Interventions focused on strengthening memory can provide long-term academic benefits.

Working memory and ageing

As people age, working memory typically declines.

This decline can affect everyday tasks, such as remembering appointments or managing finances.

However, research suggests that engaging in cognitively stimulating activities may help slow this decline.

Brain-training exercises, social interactions, and learning new skills have been shown to preserve cognitive abilities in older adults.

Factors influencing working memory

Attention and processing speed

Working memory is closely linked to attention.

When attention is divided or distracted, working memory performance suffers.

Processing speed also plays a role, as faster processing allows more efficient manipulation of information.

Enhanced focus and quick processing contribute to better memory retention and task completion.

Sleep and physical activity

Sleep is essential for cognitive function, including working memory.

Sleep deprivation impairs the brain’s ability to retain and manipulate information.

Regular physical activity has been associated with improvements in working memory and overall brain health.

Exercise promotes neurogenesis and increases blood flow to the brain, enhancing memory-related functions.

Stress and mental health

Chronic stress and anxiety can negatively impact working memory.

High cortisol levels interfere with the brain’s memory systems, reducing both capacity and efficiency.

Managing stress through mindfulness, meditation, or therapy can improve cognitive performance.

Strategies to enhance working memory

Cognitive training techniques

Several training programmes aim to boost working memory capacity.

These include:

- Brain-training apps that focus on memory games and puzzles

- Structured memory tasks that challenge recall and manipulation of information

While some studies support the effectiveness of cognitive training, results vary, and further research is needed.

Consistent practice and targeted activities tailored to individual needs often yield the best results.

Lifestyle interventions

Healthy lifestyle choices can significantly impact working memory.

Strategies include:

- Getting adequate sleep each night to support cognitive processing

- Engaging in regular exercise to enhance brain function

- Eating a balanced diet rich in brain-boosting nutrients, such as omega-3 fatty acids

Nutrients found in fish, nuts, and leafy greens play a crucial role in maintaining memory performance.

Reducing sugar intake and staying hydrated also contribute to optimal brain health.

Working memory and academic performance

Students with strong working memory skills tend to excel in areas like reading, mathematics, and problem-solving.

Working memory is critical for:

- Following multi-step instructions

- Solving complex problems

- Retaining information during exams

Efficient working memory enables students to learn new concepts faster and apply knowledge more effectively.

Supporting students with working memory challenges

Teachers and parents can implement strategies to help students improve working memory.

These include:

- Breaking tasks into smaller, manageable steps

- Using visual aids and memory prompts

- Allowing extra time for completing assignments

Incorporating hands-on activities and interactive learning can further enhance memory retention.

Encouraging regular practice and reinforcing skills in different contexts also strengthens memory.

The neurological basis of working memory

Brain regions involved

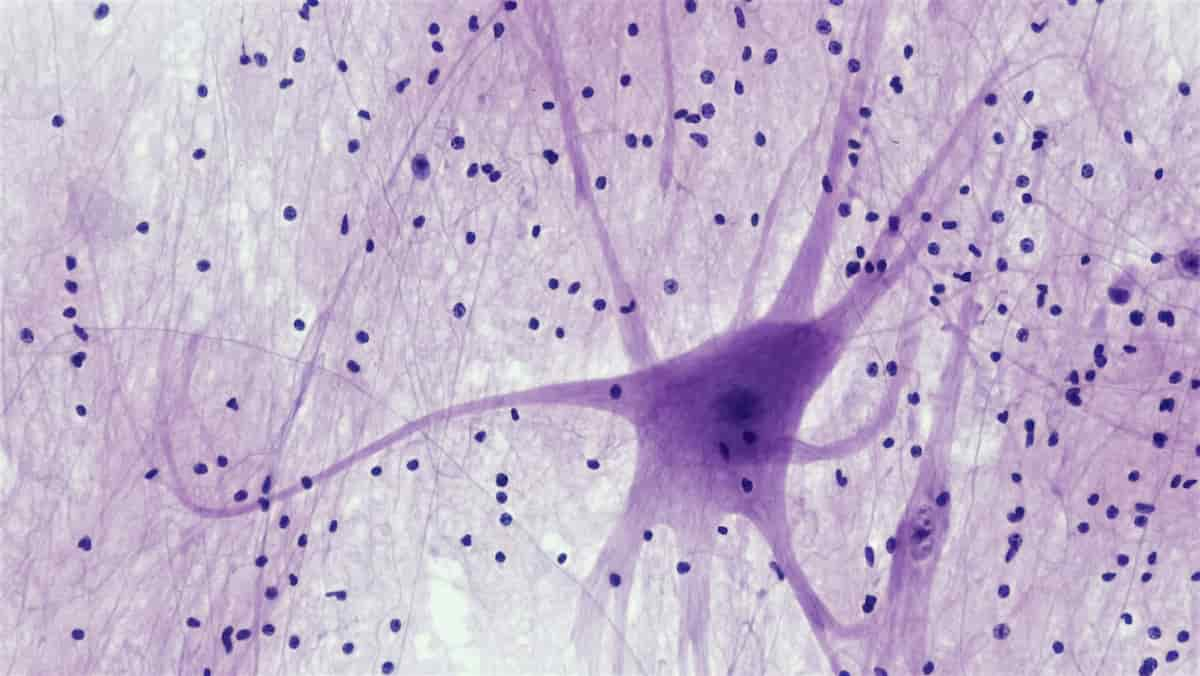

Working memory relies on several areas of the brain, primarily the prefrontal cortex.

The parietal lobes and hippocampus also contribute to memory processes.

The prefrontal cortex is responsible for decision-making, planning, and regulating thought processes.

Neural mechanisms

Neurons communicate through complex networks to store and manipulate information.

Changes in neural connectivity influence working memory capacity.

Synaptic plasticity, the brain’s ability to adapt and reorganise, plays a key role in memory development.

Working memory in clinical populations

ADHD and working memory

Many individuals with ADHD experience working memory deficits.

These challenges can lead to difficulties with organisation, time management, and academic performance.

Interventions that combine behavioural strategies with memory training can be beneficial.

Anxiety and depression

Anxiety and depression have been linked to impaired working memory.

High levels of stress hormones, such as cortisol, can negatively impact cognitive function.

Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy and relaxation techniques help mitigate these effects.

Future directions in working memory research

Emerging technologies and innovative approaches are advancing the understanding of working memory.

Potential areas of growth include:

- Developing more effective cognitive training programmes

- Exploring the role of nutrition in cognitive health

- Investigating the impact of digital media use on memory capacity

Advances in neuroimaging provide deeper insights into brain activity related to working memory.

Understanding genetic influences and tailoring personalised interventions may further enhance treatment.

Conclusion

Working memory is a fundamental cognitive skill that affects many aspects of daily life.

By understanding its components, influencing factors, and ways to enhance it, individuals can adopt strategies to improve their cognitive function and overall quality of life.

Investing in working memory development benefits both short-term performance and long-term brain health.