Research into 63 companies and their CEOs reveals an unexpected leadership factor.

Keep reading with a Membership

• Read members-only articles

• Adverts removed

• Cancel at any time

• 14 day money-back guarantee for new members

.

Research into 63 companies and their CEOs reveals an unexpected leadership factor.

This valuable and dynamic ability is linked to higher intelligence.

This valuable and dynamic ability is linked to higher intelligence.

People with above average intelligence are seen as better leaders by others, research finds.

The best IQ score for leading a group is 118.

That is 18 points higher than the average of 100 — making them smarter than around 80 percent of people.

Leaders who are around this much smarter than their followers are seen as the most effective.

However, being too intelligent is linked to worse leadership, the study also found.

It may be that highly intelligent leaders struggle to understand the challenges faced by less gifted workers.

They may also be worse at simplifying jobs and using straightforward language.

In other words, a leader who is too smart may be hard to understand.

The conclusions come from a study of 379 mid level managers working at seven multinationals.

They were rated by their peers, supervisors and subordinates, along with taking IQ and personality tests.

The results revealed that women were generally seen as better leaders, as were slightly older people.

However, the authors explain that these results hold only for mid-level managers:

“Our conclusions are limited too by the fact that the sample consisted of mid level leaders rather than company CEOs who might exhibit far more task-oriented than social-emotional leadership.

We would then expect CEOs to display much higher IQ peaks than those observed here, as well more Conscientiousness and less Agreeableness!

In partial support for this conjecture, recent research suggests that leaders in the top 1% of general intelligence are disproportionately represented among Fortune 500 CEOs.”

Another kink is that the effectiveness of a leader’s intelligence depends on the people they are leading.

More intelligent groups need even more intelligent leaders.

The authors write:

“…Sheldon Cooper, the genius physicist from “The Big Bang Theory” TV series is often portrayed as being detached and distant from normal folk, particularly because of his use of complex language and arguments.

[…] Sheldon could still be a leader—if he can find a group of followers smart enough to appreciate his prose!”

The study was published in the Journal of Applied Psychology (Antonakis et al., 2017).

The reason companies sometimes ignore people with better qualifications in favour of psychopaths.

Despite their destructive effect, narcissistic leaders are often paid more because they are better at taking credit for other people’s success.

People with this personality trait naturally emerge as leaders.

Leaders come in many different varieties, but one thing sets them apart.

What’s the best look for a leader?

What’s the best look for a leader?

When choosing a leader, people prefer a healthy complexion, but mostly ignore the appearance of intelligence, a new study finds.

The findings are based on a Dutch-led study, which looked at the unconscious influence of facial appearance on which leaders people choose for different sorts of leadership (Spisak et al., 2014).

Facial traits can provide all sorts of information about someone’s personality.

For example, a more feminine face — in both men and women — is linked to greater ‘feminine’ qualities, like cooperation.

More masculine faces, however, suggest higher levels of risk-taking.

Participants in the study were shown pictures of the same man digitally adjusted to look more or less intelligent and more or less healthy.

They had to choose the man who would do the best job as CEO of a company which different groups of participants were told had different priorities, such as aggressive competition or moving into new markets.

The results showed that over two-thirds of the time people chose the man with the healthier complexion and this was easily the more powerful influence.

Dr. Brian Spisak, who led the study, said:

“Here we show that it always pays for aspiring leaders to look healthy, which explains why politicians and executives often put great effort, time, and money in their appearance.

If you want to be chosen for a leadership position, looking intelligent is an optional extra under context-specific situations whereas the appearance of health appears to be important in a more context-general way across a variety of situations.”

The only situations in which an intelligent appearance in a leader had an effect was if the position required diplomacy or inventiveness — but it was still a healthy complexion that held sway overall.

The authors conclude that…

“…the activation of “disease concerns” in the environment exacerbates the voting tendency to prefer attractive political candidates.

Attractiveness is in part driven by cues to health and healthy leaders are likely to be exceptionally important when disease threatens the viability of the group.”

Image credit: Roger Braunstein

What’s the difference between how women see themselves and how they are seen by others?

What’s the difference between how women see themselves and how they are seen by others?

Women are rated by others as being just as effective leaders as men, and sometimes they are rated more highly, according to a new review of the research.

The conclusions are based on data from tens of thousands of leaders in studies that have been conducted over almost fifty years (Paustian-Underdahl et al., 2014).

However, when men and women each rated their own leadership, men consistently rated themselves more highly than women rated themselves.

However, when other people’s ratings were taken into account, this difference disappeared.

The study’s lead researcher, Samantha C. Paustian-Underdahl, explained:

“When all leadership contexts are considered, men and women do not differ in perceived leadership effectiveness.

As more women have entered into and succeeded in leadership positions, it is likely that people’s stereotypes associating leadership with masculinity have been dissolving slowly over time.”

In the past women were not seen as having the right qualities for leadership:

“Women are typically described and expected to be more communal, relations-oriented and nurturing than men, whereas men are believed and expected to be more agentic, assertive and independent than women.

As organizations have become fast-paced, globalized environments, some organizational scholars have proposed that a more feminine style of leadership is needed to emphasize the participative and open communication needed for success.” (Paustian-Underdahl et al., 2014).

In certain types of positions women were rated by others as more effective leaders than men:

This might be due to a “double standard of competence,” in that women have to be twice as good as men to get the top position.

Paustian-Underdahl continued:

“These findings are surprising given that men on average continue to be paid more and advance into higher managerial levels than women.”

Image credit: The picture is of

The six psychological factors that make a really great leader.

Psychological research on leadership locates the assertiveness sweet spot.

Some people believe that being an effective leader is about being tough and taking the hit to your likeability—like a drill sergeant. These sorts of leaders say things like: “It’s not my job to be liked, it’s my job to get things done.”

Others—but probably many fewer—think that being more touchy-feely will boost the positive will towards you and help get things done.

Is there any evidence for either extreme or can you have your cake and eat it?

That’s what Ames & Flynn (2007) tested with 3 groups of MBA students who filled in questionnaires about each other and managers for whom they’d worked. They looked at both social and instrumental outcomes of assertiveness: in other words, how much did people like them and how much did they get things done.

Here’s what they found:

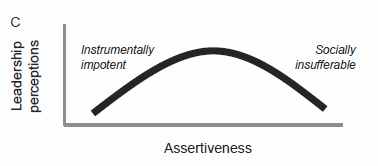

When you put both of the outcomes together you get an inverted U-shape (below; from Ames & Flynn, 2007). So that people who are low in assertiveness get less things done but people very high in assertiveness are socially insufferable.

In the middle, however, there’s a sweet spot. Whether it’s how leaders dealt with conflict, tried to influence others or motivated their teams, the assertiveness middle ground was clearly the place to be.

In the middle, however, there’s a sweet spot. Whether it’s how leaders dealt with conflict, tried to influence others or motivated their teams, the assertiveness middle ground was clearly the place to be.

And it emerged that assertiveness is vital in how we evaluate co-workers and managers. It may be too little or it may be too much, but workers’ assertiveness was complained about more than other important leadership qualities like intelligence, charisma and conscientiousness.

But when people are moderately assertive, we don’t tend to notice. In the sweet spot assertiveness seems to disappear off our personality judgement radar: if you’re doing it right, no one will notice.

So the tacit belief that you get the best results in business by riding people hard is probably wrong, as is the softly-softly approach. In particular being highly assertive may work in the short-term but in the long-term the productivity gains are small compared with the social damage that’s done.

Image credit: Subharnab Majumdar

Join the free PsyBlog mailing list. No spam, ever.