How Aging Changes What Makes You Happy (M)

“We are the sum of all the moments of our lives—all that is ours is in them.” –Thomas Wolfe

“We are the sum of all the moments of our lives—all that is ours is in them.” –Thomas Wolfe

Explore the secret to happiness in these breath-taking environments.

Explore the secret to happiness in these breath-taking environments.

People are happier in more beautiful environments, research finds.

That doesn’t just mean nature: people are also happier in characterful areas of towns and cities.

Towers, churches and cottages can make people as happy as ponds, paths and rivers.

Beautiful scenes — whether natural or man-made — allow the mind to recover, according to one prominent psychological theory.

Picturesque, bright areas with broad views help the mind to restore itself.

The finding builds on a previous study that found people also feel healthier in more beautiful places.

Dr. Chanuki Seresinhe the study’s first author, said:

“We find that people are indeed happier in more scenic environments, even after controlling for a range of variables such as potential effects of the weather, and the activity that an individual was engaged in at the time.

Crucially, we show that it is not only the countryside with which we see this association: built-up areas, which might comprise characterful buildings or bridges, also have a positive link to happiness.

Therefore, this research could be useful for informing decisions made in the design of our towns, cities and urban neighbourhoods, which affect people’s everyday lives.”

The results come from a study involving over 15,000 people who rated almost one million photos for beauty.

The data was combined with reports of people’s happiness in different places that was gathered from an iPhone app called ‘Mappiness’.

With this app, people report their happiness multiple times a day.

The results showed that people were happier when they were in more beautiful places.

Dr Seresinhe said:

“According to Attention Restoration Theory, scenes requiring less demand on our attention allow us to become less fatigued, more able to concentrate, and thus perhaps even less irritable.

Such restorative settings have often been associated with nature, and in contrast, one can imagine that a bustling urban setting such as Times Square in New York might demand our full attention.

However, we find more picturesque streets with broad views and fewer distractions might also function as restorative settings.

Settings that are more beautiful may also hold our interest for longer, thereby blocking negative thoughts.”

The study was published in the journal Scientific Reports (Seresinhe et al., 2019).

Here are 20 simple tweaks to mindset, habits and lifestyle to enhance everyday life.

High social status often brings more power, but this did not make people feel happier.

Two standard psychological techniques together help people feel more positive about life.

The saddest events in life are health problems, bereavement and large financial losses.

The saddest events in life are health problems, bereavement and large financial losses.

It takes around four years for people to recover their well-being after the saddest events in life, such as health problems, bereavement and large financial losses, research finds.

In contrast, the happiest events in life — marriage, childbirth and a major financial gain — typically only provide a boost to happiness for two years.

Many major life events have relatively little effect on happiness, including moving house and getting a new job, the study also revealed.

Dr Nathan Kettlewell, the study’s first author, said:

“Marriage, childbirth and a major financial gain produced the greatest elevation to wellbeing, however they did not lead to long-lasting happiness – the positive effect generally wore off after two years.

However, there was also an anticipatory effect for marriage and childbirth, with wellbeing increasing prior to these events.”

The study tracked the major life events of 14,000 people in Australia over 12 years.

The four most common life events are getting a new job, moving house, pregnancy and injury or illness in a close family member.

The results showed that events that had the greatest negative impact on well-being were large financial losses, health problems and the death of a partner.

Those that had the greatest positive impact were a large financial gain, getting married and having a baby.

In contrast, getting fired, being promoted and moving house had relatively little effect on well-being.

Dr Kettlewell said:

“The life events that saw the deepest plunge in wellbeing were the death of a partner or child, separation, a large financial loss or a health shock.

But even for these negative experiences, on average people recovered to their pre-shock level of wellbeing by around four years.”

The researchers looked at two different types of happiness: feeling good and life satisfaction.

Life satisfaction is how people evaluate their lives overall while happiness refers to emotion felt in the moment.

Life events like marriage and retirement made people more satisfied with their lives, but did not make much difference to felt happiness.

People having children felt quite satisfied in the first year but were significantly less happy.

Dr Kettlewell said:

“While chasing after happiness may be misplaced, the results suggest that the best chances for enhancing wellbeing may lie in protecting against negative shocks, for example by establishing strong relationships, investing in good health and managing financial risks.

And we can take consolation from the fact that, although it takes time, wellbeing can recover from even the worst circumstances.”

The study was published in the journal SSM – Population Health (Kettlewell et al., 2020).

Mismatched millions: why so many people are stuck in jobs they hate. Will artificial intelligence save the day?

“Do not spoil what you have by desiring what you have not; remember that what you now have was once among the things you only hoped for.” ~ Epicurus

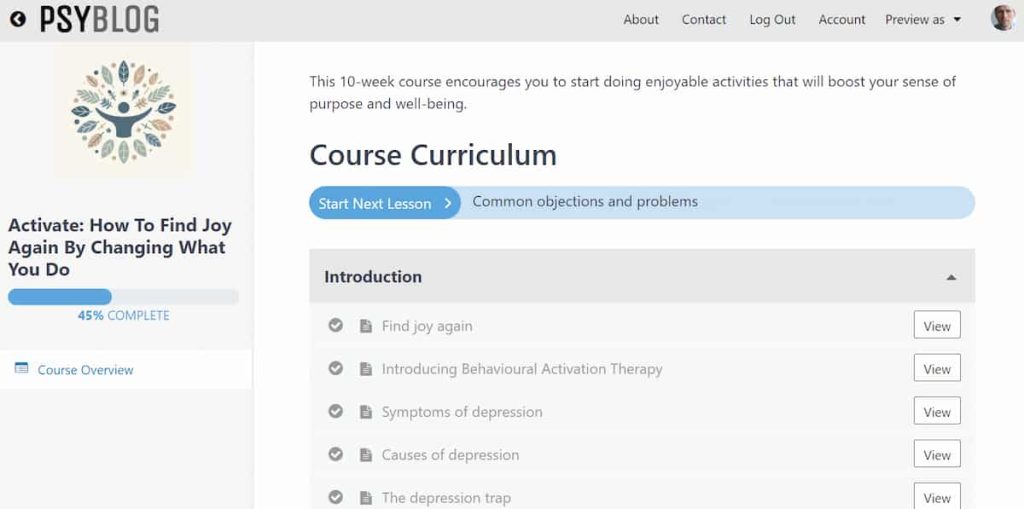

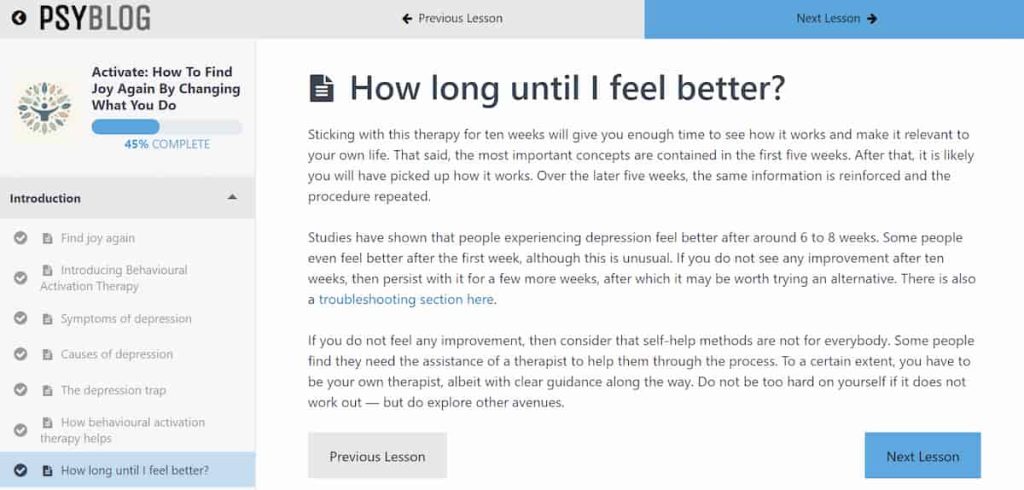

Are you feeling stuck, overwhelmed, or simply not yourself lately? It’s time to reclaim your happiness with PsyBlog’s 10-week online course, included in the Premium Membership.

Are you feeling stuck, overwhelmed, or simply not yourself lately? It’s time to reclaim your happiness with PsyBlog’s 10-week online course, included in the Premium Membership.

Activate is PsyBlog’s first online course, which is included in the new Premium Membership.

The course distils years of research and clinical experience into a practical, user-friendly 10-week program designed to help those feeling stuck or overwhelmed find joy again.

With a Premium Membership you will be able to access all 10 weeks of this course, with the first week currently now online.

The remaining parts of the course will be released week by week — keep an eye on the daily email updates for reminders.

A Premium Membership also gives you access to all members-only articles, premium content and other courses, as they become available.

Over the span of 10 weeks, “Activate: How To Find Joy Again By Changing What You Do” will guide you through:

Behavioural activation is a powerful approach that emerged from cognitive-behavioural therapy (CBT), one of the most effective methods for treating depression and improving mental well-being.

While CBT focuses on changing both thoughts and behaviours, behavioural activation zeroes in on actions, making it easier to implement and understand.

By focusing on what you do, rather than what you think, this method helps you gradually build a life filled with activities that bring you joy and satisfaction.

Research has shown that behavioural activation is just as effective as traditional CBT.

The beauty of this approach lies in its simplicity and practicality—changing behaviours is often more straightforward than changing thoughts.

As you engage in positive activities, your thoughts and feelings naturally begin to shift towards a more positive outlook.

Don’t let another day go by feeling less than your best. Take the first step towards a brighter, more joyful future.

Enroll now and unlock the tools you need to transform your life, one joyful activity at a time.

Can happiness be learned? Discover the surprising findings of a university course designed to unlock the secrets of joy.

Join the free PsyBlog mailing list. No spam, ever.