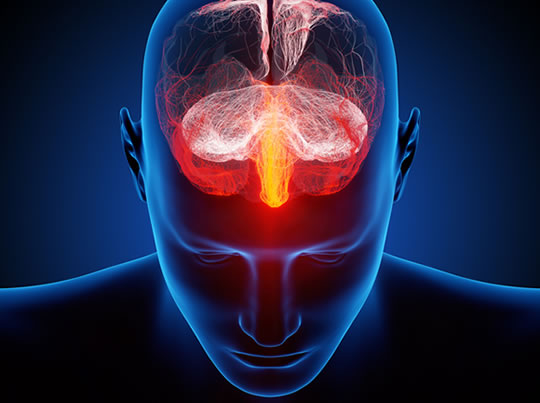

Over-the-counter painkillers change how you think, dull the emotions and dial down empathy.

Popular painkillers like ibuprofen and acetaminophen reduce people’s empathy, dull their emotions and change how people process information.

Acetaminophen is an ingredient in over 600 different medications, including being the main constituent of Tylenol.

A new scientific review of studies suggests over-the-counter pain medication could be having all sorts of psychological effects that consumers do not expect.

Not only do they block people’s physical pain, they also block emotions.

The authors of the study, published in the journal Policy Insights from the Behavioral and Brain Sciences, write:

“In many ways, the reviewed findings are alarming.

Consumers assume that when they take an over-the-counter pain medication, it will relieve their physical symptoms, but they do not anticipate broader psychological effects.”

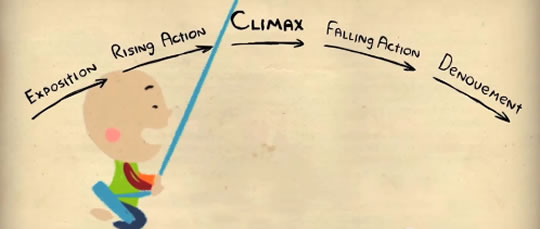

Taking over-the-counter painkillers changed how people’s brains processed information, how they experienced emotions and reacted to emotional events, the authors found.

When women take ibuprofen and acetaminophen — commonly known as Tylenol in the US and paracetamol elsewhere — it reduces the hurt caused by painful events, such as being betrayed.

The reverse pattern was seen in men: they actually felt more emotional hurt after taking these painkillers.

Both men and women showed less empathy after taking acetaminophen (Tylenol).

Other studies also showed this dulling of emotions in different ways.

People respond more moderately to unpleasant photographs after taking these painkillers — suggesting reduced sensitivity.

People taking acetaminophen also made more errors while trying to process information.

These studies suggest regulators may need to re-examine these drugs.

Among people who are depressed or who have trouble feeling positive emotions, these sorts of painkillers could be having negative effects.

The study is to be published in the journal Policy Insights from the Behavioral and Brain Sciences (Ratner et al., 2018).