Creativity research in psychology reveals 14 ways to increase imaginative and creativity thinking, discover new ideas and solve problems.

Creativity and imagination is all about finding new solutions to problems and situations.

Creativity and being original are useful skills for everyone.

And everyone is creative: we can all innovate given time, freedom, autonomy, experience to draw on, perhaps a role model to emulate and the motivation to get on with it.

But there are times when even the most creative person gets bored, starts going round in circles, or hits a cul-de-sac.

So here are 14 creativity boosters that research has shown will increase creativity:

1. Combine opposites for inspiration

Interviews with 22 Nobel Laureates in physiology, chemistry, medicine and physics as well as Pulitzer Prize winning writers and other artists has found a surprising similarity in their creative processes (Rothenberg, 1996).

Called ‘Janusian thinking’ after the many-faced Roman god Janus, it involves conceiving of multiple simultaneous opposites.

Integrative ideas emerge from juxtapositions, which are usually not obvious in the final product, theory or artwork.

Physicist Niels Bohr may have used Janusian thinking to conceive the principle of complementarity in quantum theory (that light can be analysed as either a wave or a particle, but never simultaneously as both).

◊ For insight: set up impossible oppositions, try ridiculous combinations. If all else fails, pray to Janus.

2. Take the path of most resistance

When people try to be ingenious they usually take the path of least resistance by building on existing ideas (Ward, 1994).

This isn’t a problem, as long as you don’t mind variations on a theme.

If you want something more novel, however, it can be limiting to scaffold your own attempts on what already exists.

The path of most resistance can lead to more creative solutions.

◊ For insight: because it’s the path of least resistance, every man and his dog is going up and down it. Try off-road.

3. A counterfactual mindset boosts creativity

Conjuring up what might have been gives a powerful boost to creativity.

Markman et al. (2007) found that using counterfactuals (what might have happened but didn’t) sometimes doubled people’s creativity.

But counterfactuals work best if they are tailored to the target problem:

- Analytical problems are best tackled with a subtractive mind-set: thinking about what could have been taken away from the situation.

- Expansive problems benefited most from an additive counterfactual mind-set: thinking about what could have been added to the situation.

4. Two problems are more creative than one

People solve many problems analogically: by recalling a similar old one and applying the same, or similar solution.

Unfortunately, studies have found that people are poor at recalling similar problems they’ve already solved.

In a counter-intuitive study, however, Kurtz and Lowenstein (2007) found that having two problems rather than one made it more likely that participants would recall problems they’d solved before, which helped them solve the current problem.

So don’t avoid complications, gather them all up; they may well help jog your memory.

5. Psychological distance for creativity insight

People often recommend physical separation from creative impasses by taking a break, but psychological distance can be just as useful.

Participants in one study who were primed to think about the source of a task as distant, solved twice as many insight problems as those primed with proximity to the task (Jia et al., 2009).

◊ For insight: Try imagining your creativity task as distant and disconnected from your current location. This should encourage higher level thinking.

6. Fast forward in time for originality

Like psychological distance, chronological distance can also boost creativity.

Forster et al., (2004) asked participants to think about what their lives would be like one year from now.

They were more insightful and generated more creative solutions to problems than those who were thinking about what their lives would be like tomorrow.

Thinking about distance in both time and space seems to cue the mind to think abstractly and consequently more creatively.

◊ For insight: Project yourself forward in time; view your creative task from one, ten or a hundred years distant.

7. Use bad moods to be more creative

Positive emotional states increase both problem solving and flexible thinking, and are generally thought to be more conducive to creativity.

But negative emotions also have the power to boost creativity.

One study of 161 employees found that creativity increased when both positive and negative emotions were running high (George & Zhou, 2007).

They appeared to be using the drama in the workplace positively.

◊ For insight: negative moods can be creativity killers but try to find ways to use them—you might be surprised by what happens.

8. Fight for imagination and creativity

We tend to think that when people are arguing, they become more narrow-minded and rigid and consequently less creative.

But, according to research by Dreu and Nijstad (2008), the reverse may actually be true.

Across four experiments they found that when in conflict people engaged more with a problem and generated more original ways of arguing.

Being in social conflict seems to give people an intense motivated focus. So, to get creative, start a fight.

9. Generic verbs lead to creative insights

Another boost for analogical thinking can be had from writing down the problem, then changing the problem-specific verbs to more generic ones.

What Clement et al. (1994) discovered when they tested this method was that analogical leaps are easier when problems were described in looser, more generic terms.

In this study performance increased by more than 100% in some tasks.

This is just one of a number of techniques which encourage focus on the gist of the problem rather than its specific details, which helps boost creativity.

10. Synonyms boost creativity

Just like changing the verbs, re-encoding the problem using synonyms and category taxonomies can help.

This means analysing the type of problem and coming up with different ways of representing it.

Lowenstein (2009; PDF) emphasises the importance of accessing the underlying structure of the problem in order to work out a solution.

11. Love leads to creative thinking

Forster et al. (2009) found that when experimental participants were primed with thoughts of love they became more creative, but when primed with carnal desire they became less creative (although more analytical).

While it certainly isn’t the first time that love has been identified as a creative stimulus, psychologists have suggested a particular cognitive mechanism.

Love cues us with thoughts of the long-term, hence our minds zoom out and we reason more abstractly and analogically.

Sex meanwhile cues the present, leading to a concrete analytical processing style.

For creativity, abstraction and analogy are preferred.

12. Creativity requires more than daydreaming

To increase creativity we’re always hearing about the benefits of daydreaming for incubating ideas.

It’s a nice idea that all the work is going on under the hood with no effort from us.

But you’ll notice that all the methods covered here are active rather than passive.

That’s because the research generally finds only very small benefits for periods of incubation or unconscious thought (Zhong et al., 2009).

The problem with unconscious creativity is that it tends to remain unconscious, so we never find out about it, even if it exists.

The benefit of incubating or waiting on creativity may only be that it gives us time to forget all our initial bad ideas, to make way for better ones.

Moreover, incubating for creativity only works if the unconscious already has lots of information to incubate, in other words if you’ve already done a lot of work on the problem.

So: stop daydreaming and start doing!

13. Being absurd increases creativity

The mind is desperate to make meaning from experience.

The more absurdity it experiences, the harder it has to work to find meaning and creative insights.

Participants in one study read an absurd short story by Franz Kafka before completing a pattern recognition task (Proulx, 2009).

Compared with control participants, those who had read the short story showed an enhanced subconscious ability to recognise hidden patterns.

◊ For insight: read Alice in Wonderland, Kafka’s Metamorphosis, or any other absurdist masterpiece. Absurdity is a ‘meaning threat’ which enhances creativity.

14. Re-conceptualise the problem for inspiration

People often jump to answers too quickly before they’ve really thought about the question.

Research suggests that spending time re-conceptualising the problem is beneficial.

Mumford et al., (1994) found that experimental participants produced higher quality ideas when forced to re-conceive the problem in different ways before trying to solve it.

Similarly a classic study of artists found that those focused on discovery at the problem-formulation stage produced better art (Csikszentmihalyi & Getzels, 1971).

◊ For insight: forget the solution for now, concentrate on the problem. Are you asking the right question?

Bonus radical creativity idea

If all that fails, then I’ve got one radical, bonus suggestion: move to another country and learn another language.

Maddux and Galinsky (2009) found that people who had lived abroad performed better on a range of creative tasks.

In an experimental test of this idea, Maddux et al. (2010) asked participants to recall multicultural learning experiences and found that this made people more flexible in their thinking and better able to make creative connections.

This only worked when people had actually lived abroad, not when they just imagined it.

Everyday creativity and ingenuity

Despite all the highfalutin talk of Nobel Prize winners and artists, all of these methods can be applied to everyday life.

Combining opposites, choosing the path of most resistance, absurdism and the rest can just as easily be used to help you choose a gift for someone, think about your career in a new way or decide what to do at the weekend.

‘Off-duty’ creativity is just as important, if not more so, than all that ‘serious’ creativity.

“Creativity can solve almost any problem. The creative act, the defeat of habit by originality overcomes everything.” ~George Lois

.

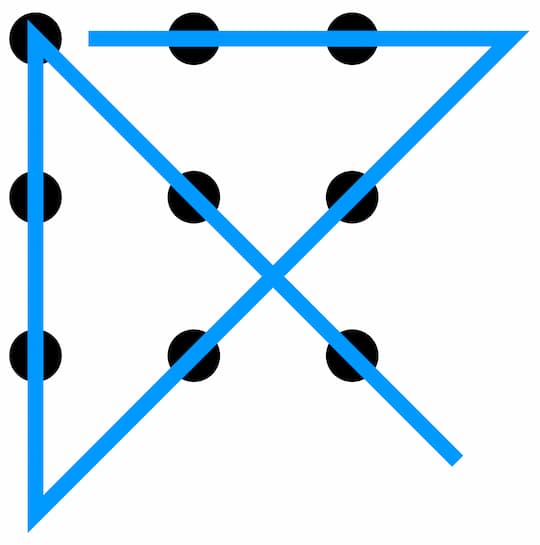

The ‘box’ that you are trying to think outside of is the implicit one formed in your mind by the dots.

The ‘box’ that you are trying to think outside of is the implicit one formed in your mind by the dots.