Rejecting a belief in free will is dangerous for society as it is linked to all sorts of antisocial behaviours, psychologists find.

Having free will in psychology means having the capacity to choose between different possible courses of action.

Chances are you believe that people have free will – I do too.

To me it seems that one moment I want cereal and soon I have it.

Next, I want to ride my bicycle and soon I am.

Later I have an itchy nose, and, in no time at all, it is scratched.

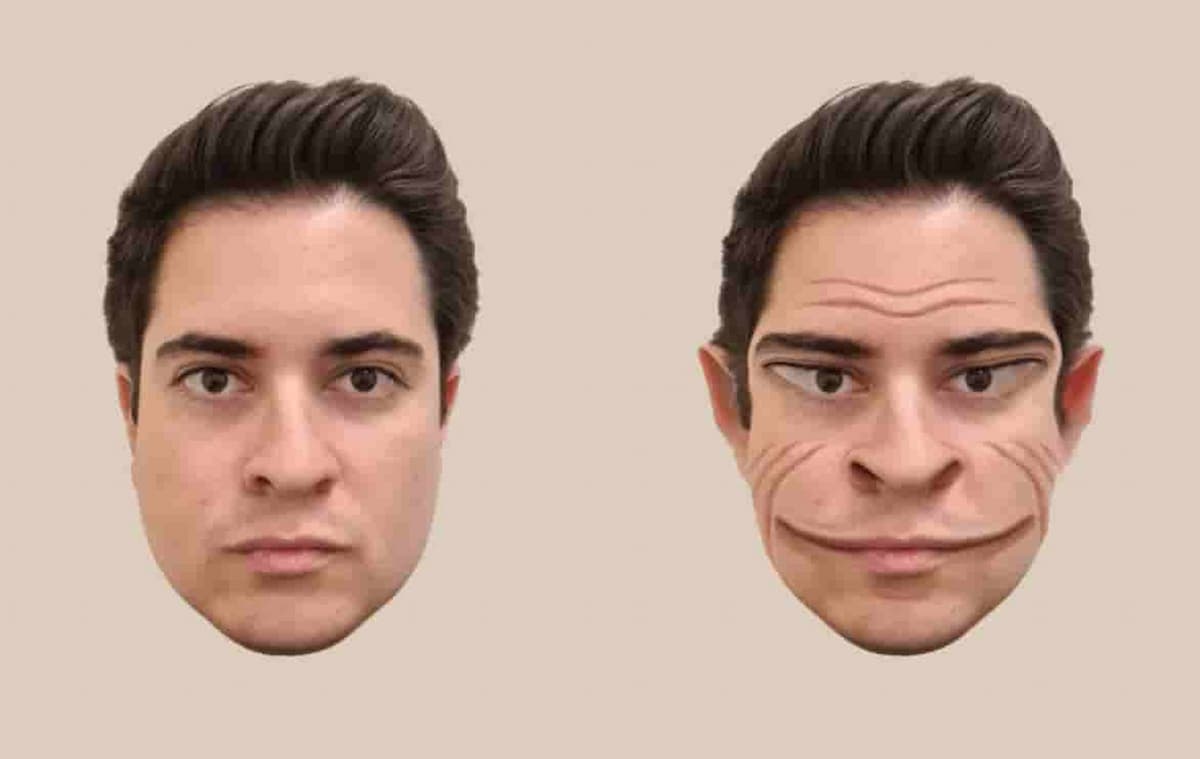

Examples of strong determinism

But, say some scientists and philosophers, this sense of agency is an illusion: you were hungry and that’s why you ‘wanted’ cereal; you were bored and fed up of being inside so you ‘decided’ to get some exercise; and as for itchy noses, well there is a biological cause for that as well.

From a determinist viewpoint each of these actions, and their causes, as well as their causes and their causes can be traced right back to my birth, then back through my parents’ lives, then right back, like clockwork, to the beginning of the universe.

The strong determinist view – that we’re locked in an unchanging web of cause and effect going right back to the big bang – is repulsive to many.

Free will means taking responsibility

And quite naturally so, as free will forms the backbone of so many of society’s structures.

The criminal justice system is built on the idea that people can choose whether to obey the law or not, therefore people who don’t obey should be punished.

Similarly many religious and/or philosophical systems of thought have the notion of free will at their heart.

Existentialist philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre emphasised the connection between freedom and responsibility.

He thought we must take responsibility for our choices, and that taking responsibility was at the heart of a life well lived.

The benefits of believing in free will

This debate about free will is so interesting – and knotted – that philosophers can’t keep away from it; but psychologists, on the other hand, perhaps sensing no end to the argument, can’t help their minds wandering away to more practical points.

They have focused more on how beliefs in free will might affect our behaviour and whether, more generally, there might be some reason why we seem predisposed to think we have it.

Baumeister, Masicampo and DeWall (2009) theorise that a belief in free will may be partly what oils the wheels of society, what encourages us to treat each other respectfully.

They explore this theory with three psychology studies, two on helping behaviours and one on aggression.

Free will and helping behaviour example

In the first psychology experiment, Baumeister and colleagues wanted to see how a belief in free will affected how much people were willing to help others.

To manipulate their belief in free will, participants read statements that either supported free will, supported determinism or had no bearing on the debate.

A separate psychology study confirmed that this really was enough to shift people’s thoughts towards determinism or towards free will.

Participants then read scenarios in which helping behaviours were explored, for example by asking about giving money to a homeless person.

They were asked to rate how much help they would provide to the people in these scenarios.

The results of the psychology study

The results showed that, as Baumeister and colleagues predicted, people whose thoughts had been pushed more towards free will were more likely to be helpful than those whose thoughts were pushed towards determinism.

So, it seems that people really are more helpful when they think they are free to choose as compared to when they believe their actions are pre-determined.

Baumeister and colleagues argue that the belief that behaviour is pre-determined encourages people to behave automatically, and often automatic behaviour is selfish.

Interestingly, there was no difference seen between the free will condition and the neutral condition.

What this suggests is that most people do already believe in free and don’t require extra encouragement.

A ‘chronic disbelief’ in free will

Of course we each differ in the amount we believe in free will and this may well affect how much help we are prepared to offer others.

A second psychology study by Baumeister and colleagues examined individual differences looking for an association between believing in free will and helping behaviours.

Consistent with the previous experiment they found that people who had a ‘chronic disbelief’ in free will were less likely to be helpful to others.

Free will and aggression example

The final psychology experiment flipped the question around: instead of looking at prosocial behaviours they looked at antisocial behaviours.

If a disbelief in free will makes people less helpful, perhaps it also makes them more likely to behave aggressively.

As before participant’s thoughts were experimentally shifted towards free will or determinism and then their aggressive tendencies were measured.

Instead of having people beating each other up in the lab, they chose a more indirect expression of aggression: putting spicy sauce on another person’s food.

Participants were introduced to a study about food preferences which, with some complicated manoeuvring, they were encouraged to think had nothing to do with previous statements they read out about free will or determinism.

Then they were told to prepare a plate of food for someone else to taste.

One of the ingredients they could choose was a hot salsa sauce.

The results of the psychology study

The experimenters were interested in whether a belief in free will affected the amount of sauce participants put on the plate.

When the participants left, the experimenters measured how much hot sauce they put on the plate.

Those who had been primed to think more deterministically had spiced up the food, on average, twice as much as those who were primed to think in terms of free will.

This seemed to have nothing to do with being more generous as they didn’t add more of other non-spicy foods, like cheese, to the plate.

Believers in free will cheat less

These experiments aren’t the first to examine how a belief in free will (or otherwise) affects our behaviour.

In a study Vohs and Schooler (2008) also found that a belief in free will seems to have a positive effect on people’s behaviour.

In that experiment participants whose disbelief in free will was encouraged were more likely to cheat on a test.

These studies, then, point out the positive effect of free will on a variety of behaviours that most people would consider beneficial.

Indeed, it seems that most of us already have a firm belief in free will and so we’re already benefiting.

Practically, the danger is that our thoughts take a more deterministic turn and we move towards more aggression and cheating and away from helping behaviours.

Compatibilism: reconciling determinism with free will

This leaves us with a serious problem.

If we think scientifically about the world then we have to accept that one thing really does lead to another; the reason I ‘decide’ to eat cereal is that I’m hungry, so in some sense the determinist is right.

But, a disbelief in free will is not only repugnant, it’s also dangerous for society.

If we don’t have free will, a perverse kind of anarchism emerges, one which seems to encourage us to act any way we choose.

After all, if we don’t have free will, then we’re not to blame for anything we do.

One way some philosophers have tried to resolve this conflict is by pointing out that determinism and free will are not necessarily incompatible.

We could have chosen to do otherwise

Using everyday notions of free will philosophers have put forward a viewpoint that tries to integrate the two (see philosopher of mind Daniel Dennett’s book ‘Freedom Evolves’ for a cognitive perspective).

Classical compatibilists argue that we have free will if we have the power and ability to do things that we want to do.

For example, say I want to go and buy a pint of milk for my cereal, and the shop is open, and I can get there, and I have money.

For a compatibilist I have free will if I can choose to go, or, alternatively, not go.

The fact that I do actually go (mainly because I’m hungry and want to eat cereal) doesn’t necessarily mean that I didn’t have the choice not to go.

Compatibilists emphasise this idea that we have free will because we could have chosen to do otherwise, even if we didn’t.

This idea that we ‘could have done otherwise’ is a powerful one, and one that appeals to our everyday experience.

It doesn’t solve the dilemma of determinism but at least it provides a stick with which to fend it off.

So when one person chooses not to help another, or chooses to behave aggressively, there must be reasons for that behaviour, many of which might appear to deny their responsibility.

Ultimately, though, the proponent of free will has to argue this person could always have chosen to do otherwise.

We have to cling to this belief, don’t we?

.