Autism: what are the numbers, the symptoms, the cause, the genetics and the cure?

Despite all that scientists have learnt about autism over the years, unfortunately the condition remains extremely mysterious.

There are so many symptoms, so many possible causes, so many possible treatments, it can be very confusing.

So here are 10 quick facts about autism to get you started.

(My apologies in advance that so many of these ‘facts’ are so woolly, but the nature of the condition is very hard for everyone, specialists included, to grasp.)

1. How many?

There are around 70 million people around the world who are autistic.

Prevalence in the US is around 1 in 100 children, maybe more.

Males are about four times more likely to have it than females.

2. The symptoms

It’s way more than just avoiding eye contact: autism is a combination of poor social, cognitive and adaptive skills.

Typical problems include language impairment, repetitive behaviours, social problems, sleep disorders, allergic reactions, seizures and abnormal behaviour in general.

Some combination of these is normally noticeable between six months and two-years-old.

But this list is still deficient: if there is a problem that a child can suffer from, then at one time or other it has been associated with autism.

That’s how confusing the condition is.

3. Is there a cure?

Autism is usually considered a lifelong condition. There is, as yet, no cure.

However, somewhere between 3% and 25% of children may lose their autistic diagnosis over the years (Helt et al., 2008).

Those most likely to recover have high intelligence, reasonably good language skills and motor development.

4. One-quarter of children are non-verbal

Set against the positive finding that some may recover, for many others the prognosis is much darker.

For example, about one-quarter of autistic children are mostly or completely non-verbal.

Perhaps as many as half of those with autism do not develop strong enough linguistic skills to get by in everyday life.

Sometimes these problems continue into adulthood.

5. It’s a spectrum

From (3) and (4), you’ll see there’s huge variability in the disorder.

That’s why it’s now known as an autism spectrum–a very big spectrum.

The ‘spectrum’ includes Asperger’s syndrome, childhood disintegrative disorder and a host of other alternative names and classifications.

6. What causes it?

Again, the real answer is that we just don’t know.

Things that have been implicated to varying degrees include: parents’ genes, the age of parents at birth, a deficient mirror-neuron systems in the brain, the ‘extreme male brain’ and so on.

None of these are definitive, though.

7. Incredible genetic complexity

There are literally hundreds of different genes that have been implicated to a greater or lesser extent (mostly to a lesser extent) in the development of autism.

As of writing, the autism database currently lists 573 genes thought to be related to autism.

Needless to say, that makes it exceedingly complex to study.

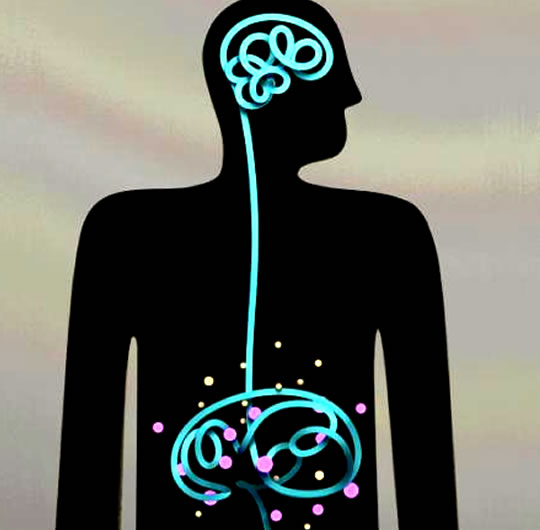

8. Cortical under-connectivity

You might be starting to think: is there anything at all you can definitively tell me about autism?

Well, one relatively new theory about autism–that it results from cortical under-connectivity–is promising.

In other words: in autism, the various parts of the brain do not talk to each other as efficiently and effectively as in a typical brain. The individual skills are there, but they are not fully integrated into a whole.

Once again, though, this is only a theory.

9. Savant syndrome

A small proportion of those with autism, around 10%, have savant syndrome.

These people can have extraordinary abilities in some limited areas, such as highly advanced mathematical or musical skills, improved visual acuity and visuospatial abilities.

Among people with autism, though, these are the exception rather than the rule.

10. What’s the treatment?

All sorts of treatments for autism have been tried, both chemical and behavioural.

Among the chemical treatments, various drugs with frightening names like Risperidone and Ziprasidone have been found to help somewhat; but these do not address the core autistic problems of social and communicative dysfunction.

Amongst behavioural approaches the most useful seem to involve play, those which focus on motor skills and the use of picture exchange for communication (McCleery et al., 2013).

Unfortunately most studies in this area are badly designed so we don’t have strong scientific evidence of what works.

→ This article is partly based on the excellent review of 1,300 different studies of autism by Hughes (2009).

Image credit: hepingting

Having now seen the excellent documentary on the autistic savant, Daniel Tammet, and noting the subject’s popularity, I’ve done a little Googling to get some more information for you…

Having now seen the excellent documentary on the autistic savant, Daniel Tammet, and noting the subject’s popularity, I’ve done a little Googling to get some more information for you…