It is remarkably easy to disguise yourself — indeed, to make yourself look unrecognizable, research finds.

Simple disguises, like a new hairstyle and makeup, are surprisingly effective at making people unrecognizable, research finds.

Makeup, hair style and colour and even facial hair growth or removal can make someone difficult to recognise.

For the study, models were recruited and told to try and change their appearance — to look unrecognizable.

Hats and dark glasses were not allowed as these are prohibited in real-life security settings.

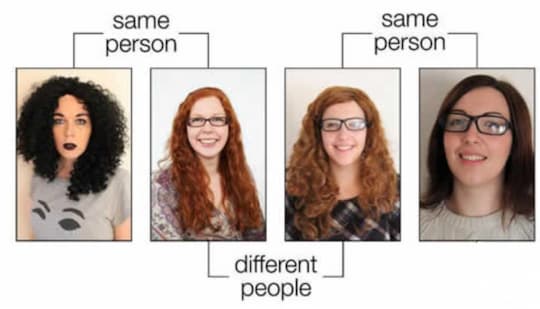

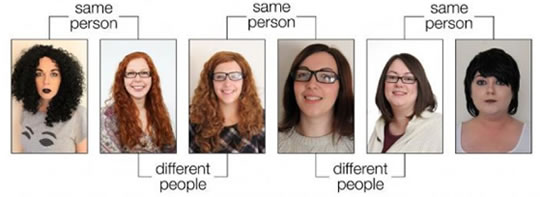

Here are some examples:

The results showed that disguises reduced people’s ability to spot the same person by 30 percent.

This was despite the fact that they were warned the target’s appearance may have changed.

Participants were only able to see through disguises when they knew the person well.

Dr Rob Jenkins, study’s co-author, said:

“We shouldn’t be complacent about deliberate disguise in criminal and security settings. When someone puts their mind to concealing their identity, it can be very effective.

Familiarity with the people who are disguising themselves improves accuracy.

When you are unfamiliar with a face you are easily fooled by superficial changes in hairstyle or colouration.

However, when you ‘know’ a face you tend to rely more on internal facial features — the eyes, nose and mouth — which are much harder to alter.”

Evasion is the best way to make yourself look unrecognizable

The most effective form of disguise, to make people look unrecognizable, was trying not to look like yourself.

This is known as an evasion disguise.

In comparison, impersonating someone else was not as effective.

Dr Eilidh Noyes, the study’s first author, said:

“With evasion disguise, you can change your appearance in any way you like.

With impersonation, you can only change your appearance in ways that resemble your target, so your options are much more constrained.

Deliberate disguise poses a real challenge to human face recognition.

The next step is to test automatic face recognition on the same tasks.”

The study was published in the Journal of Experimental Psychology: Applied (Noyes & Jenkins, 2019).