We hear a lot about the benefits of being creative but less about the dark side of creativity.

I recently wrote about why people secretly fear creative ideas, which hints at a dark side, but what about creative people themselves? Do they pay a price for their creativity?

Psychological research has only recently begun examining the dark side of creativity but it’s already turning up some interesting findings. Here are some of my favourite insights.

Liars

An alien observing humans for the first time might wonder why we pay people to lie to us. We would have to explain that we call novels, TV shows and films ‘fiction’, not lies.

Then we’d concede that sometimes we enjoy being lied to, especially when the lies are much more entertaining than reality.

Given all the practice they get, we might expect, then, that creative people should be better at lying.

And, indeed, this seems to be true: Walczyk et al. (2008) tested it by giving participants a series of everyday dilemmas to solve. Highly creative people told more and better lies than those who were less creative.

Arrogant

On the positive side, creative people are generally open to new experiences, but how easy are they to get along with?

Until now much of the research on agreeableness, one of the five fundamental aspects of personality, has been mixed.

New research, though, has looked at two sub-types of agreeableness (Silvia et al., 2011). This found no association between agreeableness and creativity, but a strong negative association with honesty-humility.

In other words, creative people tend to be arrogant.

Distrustful

Is there a link between thinking distrustful thoughts and increased creativity?

Consider this: being distrustful means being more likely to distrust surface appearances and have a desire to work out what is really going on. In other words distrust breeds a sort of ‘what-if’ mindset: exactly the sort of mindset associated with creativity.

Distrust may also breed flexibility in thinking. Instead of taking things at face value, people with suspicious minds try to see things from different angles. That’s yet another marker of creativity.

When Mayer and Mussweiler (2011) tested this idea experimentally they found good evidence to support it. Participants who primed with the idea of being distrustful came up with more creative ideas and showed greater cognitive flexibility.

But crucially these results were only found when participants were being privately creative. When people thought creative ideas would be made public, distrustful thoughts didn’t increase creativity.

Perhaps that’s why it’s hard to spot creative people. They are more likely to be distrustful of others and so keep their creative ideas to themselves.

Evil

So far creative people have been characterised as arrogant, distrustful and good liars but not actually evil. But perhaps there is something to the evil genius stereotype?

Across a series of studies Gino and Ariely (2011) found that creative people displayed all sorts of dishonest traits:

- Creative people were more likely to cheat on a game in the lab,

- Creative people were better at justifying their dishonesty afterwards,

- Creativity was more closely associated with dishonesty than intelligence.

While creativity produces all sorts of positive, beneficial outcomes, it also allows people to cheat more easily, and to cover up their cheating behaviour.

Criminal

Let’s stop beating around the bush: does being creative help you become a master-criminal?

There are certainly examples of creative criminals. Shirley Pitts was a famous British shoplifter who got around the security tag system by simply lining her carrier bag with metal foil. She could then put what she liked in her bag and walk out without the alarm going off.

But that may well be an unusual exception as there’s little strong evidence that creativity is unusually high amongst criminals (Cropley & Cropley, 2011). On average criminals show relatively low levels of creativity, along with a lack of social conformity and low levels of inhibition.

However there is some evidence that when it comes specifically to crime, criminals are creative. After all, it is their job.

Or maybe the really creative criminals are just too creative to get caught…

Crazy

A strong link exists in the popular imagination between madness and creativity. The evidence, though, is more equivocal.

Certainly creative people score higher on psychoticism, meaning they tend to be more cold, antisocial, egocentric and low in empathy. But generally this is balanced out by high self-esteem, high intelligence and the ability to keep their worst excesses in check.

It also depends on the type of genius you are. On average mental health is best amongst creative geniuses who are natural scientists (like physicists and chemists), is worse amongst social scientists (including psychologists), worse still in the humanities and is at its lowest in the arts (Simonton, 2009).

Simonton argues that creative geniuses aren’t necessarily crazy, a better word to describe them is eccentric.

Dark side

So creativity isn’t all upside. Creative individuals are more likely to be arrogant, good liars, distrustful, dishonest and maybe just a little crazy—OK, let’s call it unusual or eccentric.

But what would the world be like without its creative eccentrics? I’ll tell you: a very boring place.

Still, perhaps you’ll think twice the next time you admit how creative you are!

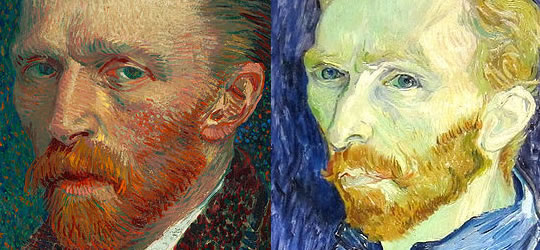

Image credits: Wikipedia & 2, 3 (details from self-portraits by Vincent Van Gogh)