Social identity theory explores how people define themselves based on their group memberships and how these identities influence behaviour, relationships, and societal structures.

What is social identity theory?

Social identity theory, developed by Henri Tajfel and John Turner in 1979, is a framework that explains how individuals derive a sense of self from their group memberships.

These groups may include categories like nationality, ethnicity, gender, social class, political affiliation, or professional identity.

The theory posits that our social identities complement our personal identities, shaping how we perceive ourselves and interact with the world.

A significant premise of the theory is that individuals strive to achieve a positive self-concept.

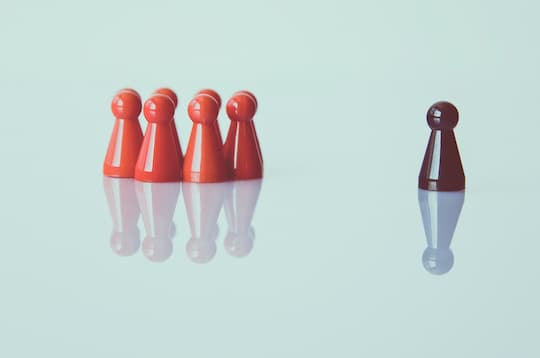

This is often achieved by favourably comparing the groups to which they belong (in-groups) with those they do not (out-groups).

The core principles of social identity theory

Social categorisation

Social categorisation is the process of dividing people into groups based on shared characteristics.

This mental shortcut helps us organise social environments but can also lead to stereotyping and overgeneralisation.

By categorising, we simplify complex interpersonal dynamics, but we also risk creating rigid in-group and out-group distinctions.

Social identification

Once categorised, individuals adopt the identity of the group they belong to.

This means that their self-concept aligns with the group’s values, norms, and behaviours.

For example, identifying as a feminist might lead someone to support policies promoting gender equality actively.

Social identification often fosters a sense of belonging and emotional attachment to the group.

Social comparison

Social comparison involves evaluating one’s group against others to enhance self-esteem.

If the in-group is perceived as superior to out-groups, members gain a positive sense of self.

However, when out-groups are seen as a threat or inferior, it can lead to prejudice, discrimination, or even conflict.

This process explains phenomena like nationalism or rivalry between sports teams.

Applications of social identity theory

In-group favouritism and out-group bias

In-group favouritism occurs when people preferentially treat members of their group over those in out-groups.

This behaviour can manifest in many ways, from hiring decisions to resource allocation.

Out-group bias, on the other hand, often leads to stereotyping, prejudice, and discrimination.

Conflict and cooperation

Social identity theory has been instrumental in explaining intergroup conflicts, such as ethnic tensions, political divisions, or workplace competition.

It also highlights how shared identities can foster cooperation, as seen in movements advocating for climate change or social justice.

Case studies and real-world examples

Minimal-group studies

One of the foundational experiments in social identity theory was Tajfel’s minimal-group paradigm (Tajfel et al., 1971).

Participants were assigned to groups based on arbitrary criteria, such as a preference for a painting.

Despite the lack of meaningful connection, individuals showed a strong tendency to favour their group, allocating more resources to in-group members.

This demonstrated that even minimal conditions are sufficient for in-group bias to emerge.

Social identity in the workplace

In professional settings, employees often identify with their organisations, departments, or teams.

Strong social identity within a group can enhance collaboration and morale.

However, it may also lead to intergroup conflicts, such as rivalry between departments, if boundaries are too rigid.

Political and social movements

Social identity theory explains why individuals rally around political ideologies or social causes.

By identifying with a group advocating specific values or goals, individuals find purpose and belonging.

This has been evident in movements like Black Lives Matter or the fight for LGBTQ+ rights.

Challenges and criticisms of social identity theory

Social identity theory is not without its limitations.

Critics argue that it oversimplifies the complex nature of individual and group interactions.

For example, the theory often assumes that group boundaries are static, ignoring how identities can be fluid and situational.

Others suggest that the theory does not fully account for personal factors, such as individual agency, that influence behaviour beyond group affiliations.

Moreover, some research questions whether in-group bias is as universal as the theory suggests, pointing to cultural variations in how social identity is expressed.

Expanding the theory: Intersectionality and beyond

Intersectionality

Intersectionality adds depth to social identity theory by recognising that individuals belong to multiple groups simultaneously.

A person might identify as a woman, an ethnic minority, and a member of the LGBTQ+ community, each contributing to their unique experiences.

This concept, introduced by Kimberlé Crenshaw, highlights how overlapping identities create unique forms of privilege or oppression.

The digital age

In the era of social media, social identity has taken on new dimensions.

Online communities allow people to form identities beyond physical boundaries, fostering connections across the globe.

However, the anonymity of the internet can also amplify polarisation and group conflict.

Practical strategies for navigating social identities

- Encourage dialogue: Open conversations between groups can reduce stereotypes and foster understanding.

- Promote shared goals: Identifying common objectives can mitigate conflict and build collaboration.

- Cultivate self-awareness: Recognising one’s biases and assumptions is the first step in overcoming them.

- Celebrate diversity: Emphasising the value of multiple perspectives can enhance creativity and innovation.

Conclusion

Social identity theory provides a robust framework for understanding how group memberships shape individual behaviour and societal dynamics.

From explaining prejudice and discrimination to fostering belonging and purpose, its applications are far-reaching.

By appreciating the nuances of social identity, we can better navigate the complexities of modern, interconnected societies.