Why some memories last a lifetime and others are quickly forgotten.

Memories that last a lifetime need to be linked to lots of other memories, plus they need to be a bit weird.

These are the two key components of memories that have the potential to last a lifetime.

Professor Per Sederberg, an expert on memory, thinks the idea of peculiarity is vital to understanding memory:

“You have to build a memory on the scaffolding of what you already know, but then you have to violate the expectations somewhat.

It has to be a little bit weird.”

This ‘scaffolding’ means connections to other memories.

For example, memories of our childhoods are linked to lots of other memories about our families and the places we lived.

And which are the stories we remember best — the ones that stand out?

Of course, it is the ones where something unusual happened: when Grandad told you he was in a band years ago and astonished you by playing the guitar.

It is when you were cycling home and happened to pass your mother in the street wearing a dragon costume and holding a cricket bat.

How memories are stored and retrieved

In one of Professor Sederberg’s studies people wore smartphones around their necks for a month.

These automatically took photos at random intervals.

Later, they relived these memories in the brain scanner so researchers could see where and how the memories were stored and retrieved.

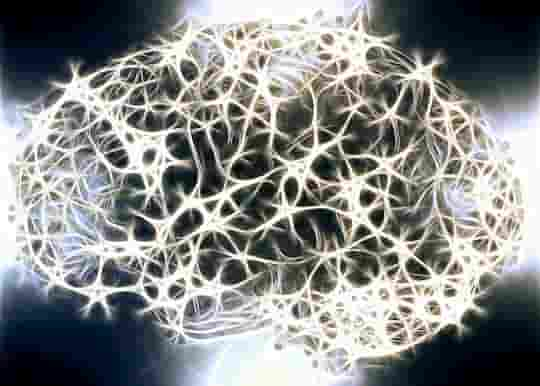

Think of all your memories as being like a vast network, Professor Sederberg said:

“If we want to be able to retrieve a memory later, you want to build a rich web.

It should connect to other memories in multiple ways, so there are many ways for our mind to get back to it.

You want to have a lot of different ways to get to any individual memory.”

Memorable experiences often happen in familiar contexts, but have some peculiar, unpredictable aspect, said Professor Sederberg:

“Those peculiar experiences are the things that stand out, that make a more lasting memory.”

This is why some memories last a lifetime and others are quickly forgotten.

Professor Sederberg was speaking at the Cannes Lions Festival of Creativity in France on June 19. The study referenced was published in the journal PNAS (Nielson et al., 2015).