The definition of deindividuation is when aspects of a situation cause people’s sense of themselves to recede, allowing them to change their behaviour.

Deindividuation in psychology is one of the reasons that people behave differently in a crowd.

When in a crowd people experience deindividuation: a loss of self-awareness.

When deindividuation takes hold people can feel less responsibility and may become anti-social or even violent.

Deindividuation definition

The psychologist Leon Festinger was the first to use the term deindividuation in a 1952 paper.

Festinger wrote that deindividuation in a group or crowd brings about a loosening in people’s behaviour.

People often enjoy being in groups which are deindividuated as they lose their sense of self.

Common examples of deindividuation are:

- When people are dancing in a nightclub, they move and behave in ways they never would in other situations.

- The online disinhibition effect causes people to behave in different ways when they are online than when they are interacting face-to-face.

- People in military units are conditioned to behave in ways that would not be normal elsewhere.

Example of deindividuation research

Psychologists have investigated deindividuation in a variety of ways.

One of those is in the context of cheating and how deindividuation affects it.

People will cheat for all sort of different reasons in all sorts of different ways — in love, in their finances and at work — but social psychologists are particularly interested in the general features of situations in which people cheat.

It’s this question that inspired Professor Ed Diener and colleagues in the 1970s to carry out a classic social psychology study of children’s honesty at Halloween.

Trick or treat?

Diener and colleagues monitored 27 houses in Seattle on the evening of Halloween, as kids came trick-or-treating (Diener et al., 1976).

Just inside the door on a table were two bowls, one filled with candy bars, another with pennies and nickels.

As children arrived in their costumes they were told to take one candy bar each, but not to touch the money.

The host then told the children she had to go back to her research in another room.

Actually, though, she was looking through a peep-hole in the door to see how much candy and/or money they would take.

But this wasn’t just a test of the kids honesty, it was a test of how various situational factors would affect what they did.

Before leaving the room, each of the hosts in each of the houses created a number of different experimental conditions.

The three major factors the experimenters wanted to examine were the effect of being in a group, anonymity and shifting the responsibility for any cheating:

- Groups: children naturally arrived either alone or in groups (so this condition was only quasi-experimental).

- Anonymity: sometimes the kids were asked by the host for their names and addresses, other times not.

- Shifted responsibility: sometimes all the children were told that the smallest child the host could see was responsible if any extra candy or money was taken.

Over the night 1,352 children entered the 27 houses across Seattle, some alone and some in groups, many emboldened by their Halloween costumes.

In each house the host, after the experimental manipulation, left the room and watched the children, waiting to see how the anonymity and responsibility shifting would affect whether they cheated, and by how much.

Anonymity and deindividuation

The good news is that overall, across all the conditions, about two-thirds of the children were completely honest and didn’t take even a single extra candy bar or touch the pennies and nickels.

But the effects of anonymity, being in a group and responsibility shifting were dramatic:

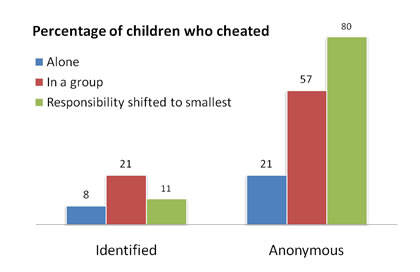

As you can see, when children came alone and were identified, only 8 percent cheated.

However when they came in a group, were anonymous and the responsibility for any cheating had been shifted to the smallest child, the average rate of cheating shot up to 80 percent.

The results suggested that each of the factors were not just additive but interacted with each other to encourage an even larger percentage of children to cheat.

The researchers teased out some further intriguing subtleties from the data they collected.

They were also interested in why the children cheated: was it just because they were in a group, or was it also because the leader cheated and the others copied?

Their results suggested there was indeed a modelling effect because in groups where the first child cheated, the other children were also more likely to cheat.

4 factors predicting cheating

This experiment is a powerful demonstration of deindividuation: when aspects of situations cause people’s sense of themselves, including their ethical and moral codes, to recede and allow them to be easily influenced by the actions of others.

Deindividuation may be at least partly responsible for social loafing, people’s tendency to slack off when working in a group.

But social loafing is the least of the charges ranged against deindividuation.

The phenomenon has been blamed for all kinds of social disorder, especially the antisocial, destructive behaviour sometimes seen in crowds (although according to some scholars the combustibility of crowds has been exaggerated, cf. 7 myths of crowd psychology).

Whatever the judgement on deindividuation, this classic social psychology study does give us four specific situations which make people more likely to cheat:

- when in a group,

- when anonymous,

- when they can copy someone else

- and when responsibility can be shifted elsewhere.

It also demonstrates that these factors can interact with each other to make it even easier for cheating to occur.

.