Vessels discovered in the brain that were thought not to exist — could revolutionise study of neurological diseases like Alzheimer’s.

The brain is directly connected to the immune system by vessels previously thought not to exist, new research reports.

The finding means the textbooks will have to be rewritten.

Discovery of the vessels may also revolutionise the study of neurological diseases like Alzheimer’s and autism.

Professor Jonathan Kipnis, who led the research, was initially sceptical about the results:

“I really did not believe there are structures in the body that we are not aware of.

I thought the body was mapped.

I thought that these discoveries ended somewhere around the middle of the last century.

But apparently they have not.”

The vessels are located in the meninges — the membrane that surrounds the brain and spinal cord.

The vessels run near major blood vessels, which partly explains why they have been so difficult to find.

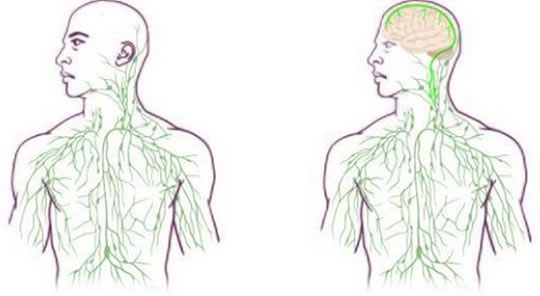

The left-hand image below shows the old map of the lymphatic system and the updated version is on the right.

The discovery will likely have profound implications for how scientists study the neuro-immune system, Professor Kipnis said:

“Instead of asking, ‘How do we study the immune response of the brain?’ ‘Why do multiple sclerosis patients have the immune attacks?’ now we can approach this mechanistically.

Because the brain is like every other tissue connected to the peripheral immune system through meningeal lymphatic vessels.

It changes entirely the way we perceive the neuro-immune interaction.

We always perceived it before as something esoteric that can’t be studied.

But now we can ask mechanistic questions.

We believe that for every neurological disease that has an immune component to it, these vessels may play a major role.

Hard to imagine that these vessels would not be involved in a [neurological] disease with an immune component.

In Alzheimer’s, there are accumulations of big protein chunks in the brain.

We think they may be accumulating in the brain because they’re not being efficiently removed by these vessels.”

The study was published in the journal Nature (Louveau et al., 2015).

Network brain image from Shutterstock and lympatic system image from University of Virginia Health System