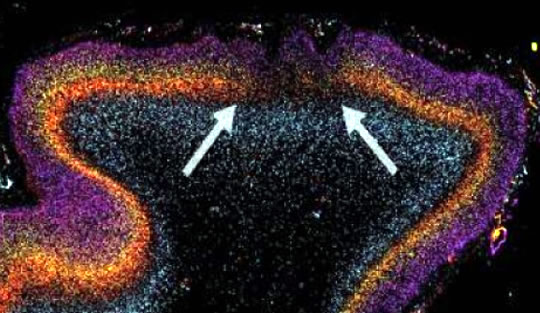

Arrows show areas of disorganised neurons in the brains of autistic children.

A new analysis of children’s brain tissue has revealed that autism begins during pregnancy with patches of disorganised neurons.

The study, to be published in the New England Journal of Medicine, compared 25 genes in the post-mortem brain tissue of children with and without autism (Stoner et al., 2014).

What they found was focused disorganisation in how the autistic brain forms.

The Director of the Autism Center of Excellence at UC San Diego, Professor Eric Courchesne, explained:

“Building a baby’s brain during pregnancy involves creating a cortex that contains six layers.

We discovered focal patches of disrupted development of these cortical layers in the majority of children with autism.”

These six layers of the brain each have their own type of brain cells and connectivity.

Each has a major role: one layer becomes the frontal cortex, the part of the brain most associated with higher-level processes like making plans and understanding complex social situations, amongst many others.

Another layer becomes the temporal cortex, the part of the brain associated with language, along with other complex functions.

The study found that, in children with autism, key genetic markers were missing, indicating that the development of the crucial six layers of the brain, with specific types of brain cells and connectivity, had been disrupted.

These early developmental defects were most common in the temporal and frontal cortex, perhaps helping to explain why children with autism have problems with language and social situations.

In comparison, the visual cortex, which is associated with perception, was largely free of disrupted development.

Perception is not an area in which children with autism normally have problems.

Another of the study’s authors, Ed S. Lein, continued:

“The most surprising finding was the similar early developmental pathology across nearly all of the autistic brains, especially given the diversity of symptoms in patients with autism, as well as the extremely complex genetics behind the disorder.”

The authors say that in children with autism the brain may be able to rewire connections to combat these disrupted cortical patches.

Courchesne added:

“The finding that these defects occur in patches rather than across the entirety of [the] cortex gives hope as well as insight about the nature of autism.”

Image credit: Rich Stoner, Ph.D., University of California, San Diego