Reading and writing from left to right is a skill so well-practised, so ingrained in language, that it’s easy to ignore. Yet, according to some research, the direction in which language flows could have implications that spread into many other areas of our experience.

Consider that people are often found to envisage time flowing in a line from left to right; to look at objects like art works from the left to the right; and to imagine numbers from 1 to ∞ laid out from left to right.

There is even something about the very movement from left to right that grabs the attention and holds it. Research finds that people or objects moving from left to right are perceived as having greater power (Maass et al., 2007):

- Soccer goals are rated as stronger, faster, even more beautiful when the movement of the scorer is from left to right, rather than right to left.

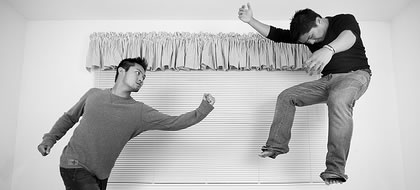

- Film violence seems more aggressive, more painful and more shocking when the punch is delivered from left to right, compared with right to left.

- Cars in an advert are rated as stronger and faster when they are moving from left to right, rather than right to left (take note advertising executives!).

Perhaps it’s no coincidence that athletes, cars and horses are all usually shown on TV reaching the finishing line from left to right.

Subject, verb, object

It seems likely that this left to right bias has its roots in language (although not everyone agrees, cf. Chatterjee, 2001). Evidence for this comes from people who speak languages written from right to left like Arabic or Urdu who, sure enough, display the same bias, but in the opposite direction.

There is another left to right bias in the basic syntax of language: the vast majority of languages describe events in the order subject, verb, object (with the notable exception of the passive tense).

Together these two facts mean we not only look to the left first, but we also expect the subject to be on the left, and the object to its right. Subjects are by definition active ‘do-ers’ while objects are the passive receivers of the do-ers’ actions.

Adam and Eve

This led Dr. Anne Maass and colleagues at the University of Padova, Italy to a number of fascinating predictions (Maass et al., 2009). First, they said, people will tend to see objects or people that appear on their left as having more ‘agentic’ properties – in other words the left is associated with power, decisiveness and action, while the right-hand-side less so.

Second they thought that males stereotypically – and I stress stereotypically before the hate mail flows – have more agentic properties than females. Therefore if they examined pairs of men and women pictured together, the man would be more likely to appear on the left side of the picture and the woman on the right.

Searching Google Images they tested the theory with pictures of a well-known couple: Adam and Eve. Their prediction was borne out as Adam was on the left in 62% of pictures, suggesting he was seen as more agentic than Eve.

Marge and Homer

But what about couples where stereotypes begin to break down? To test this 134 people were asked to give agentic ratings to three more pairs of famous fictional couples: The Flintstones, the Simpsons and the Addams family. Here’s what they got:

- Fred and Wilma Flintstone came out about equal.

- Marge and Homer Simpson also came out about equal.

- Gomez Addams was perceived as more agentic/active/decisive than Morticia Addams.

So unlike Gomez Addams, Homer Simpson and Fred Flintstone are not seen as old-fashioned patriarchs.

When they searched for pictures of the couples it turned out that both Fred Flintstone and Homer Simpson were no more likely to be depicted to the left of their wives than to the right. But Gomez Addams appeared on the left in 82% of all the representations found by the researchers. This supported their theory: being on the left did show a relationship with the perceived agency of the characters.

Ping pong

The problem with the research so far is that there are all sorts of uncontrolled factors. It may be that Adam and Gomez Addams tended to be depicted on the left of the picture for a reason other than agency. Therefore Maass and colleagues carried out another study to test their theory.

In this one 40 participants were asked to draw female and male teams playing each other at ping pong, basketball, draughts and volleyball. They also completed questionnaires that tested their endorsement of stereotypical beliefs about men and women.

What they found was that people who thought women were more agentic than men tended to put the women’s team on the left while those who thought men more agentic tended to put the men’s team on the left. This is further support for the idea that we associate the left with decisiveness, action and productivity, and the right less so.

It seems that this effect is not just about men and women either. In another experiment Mass and colleagues used pictures of young versus old people, predicting that young people would be seen as more agentic, which is exactly what they found.

Best cheek forward

The left to right effect is usually quite subtle but it can probably be spotted in all sorts of contexts, such as how we present ourselves to others. One neat study by Nicholls et al. (1999) analysed paintings of scientists and found that when they were posing ‘as scientists’ they presented their right cheek, thereby creating a left to right dynamic for the viewer of the painting. But, when posing for a family portrait, they presented their left cheek, reversing the trend, perhaps trying to create a more passive, domestic image of themselves.

Collectively these studies, if correct, suggest that the left to right bias from language influences how we perceive the world, how we depict others and perhaps even how we present ourselves.